Ibraimo Alberto

Ibraimo Alberto clearly remembers his arrival at Berlin Schönefeld: it is 16 June 1981, he just turned eighteen. He is keen on learning a lot, wants to study sports in the DDR. But things turn out differently: he is assigned to train as a butcher in the Berlin meat processing plant VEB Fleischkombinat Berlin. Soon after his arrival Ibraimo starts training as a boxer.

On the wings of independence

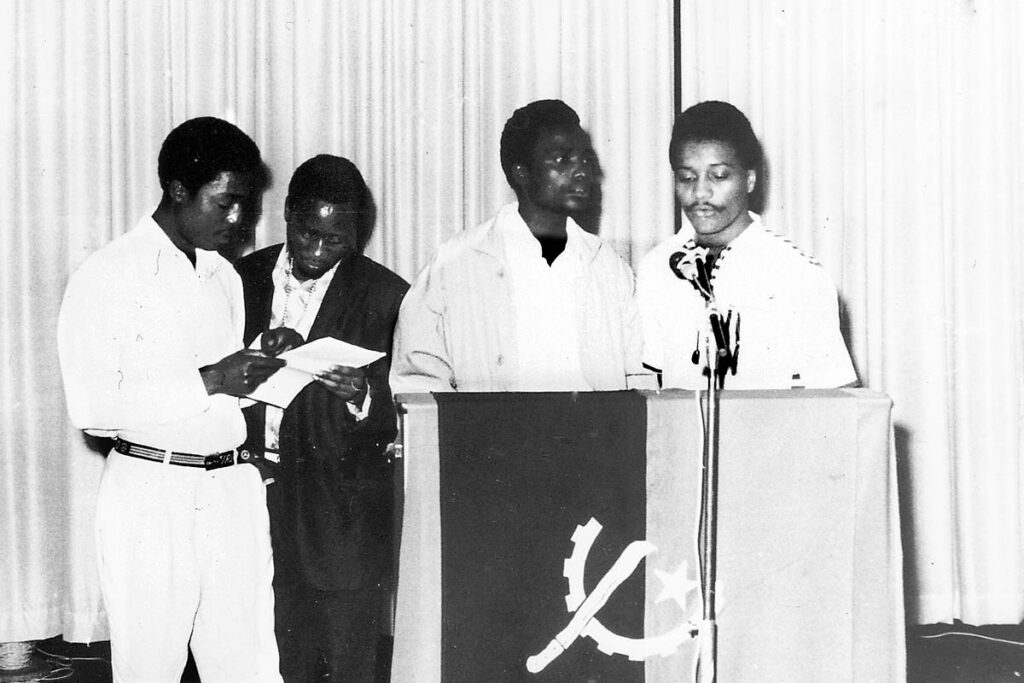

During his childhood, Ibraimo Alberto’s native Mozambique is still a Portuguese colony. Slavery-like labor conditions and political oppression dominate the lives of many. Since the early 1960s a liberation movement is leading the armed struggle against the colonial power. It is not until 1975 that Mozambique becomes independent.

Ibraimo grows up in a village. Black rural children are not supposed to receive a school education. Nevertheless he manages to attend school beyond the fourth grade. There he learns about the option of going to the GDR for an education. He hopes to be able to advance his education there, so that later he can contribute with his qualification to the development of Angola, which has only been independent for a few years.

One was only allowed to take one pair of pants and one shirt. Only three of us went.

Ibraimo Alberto, Berlin 2022

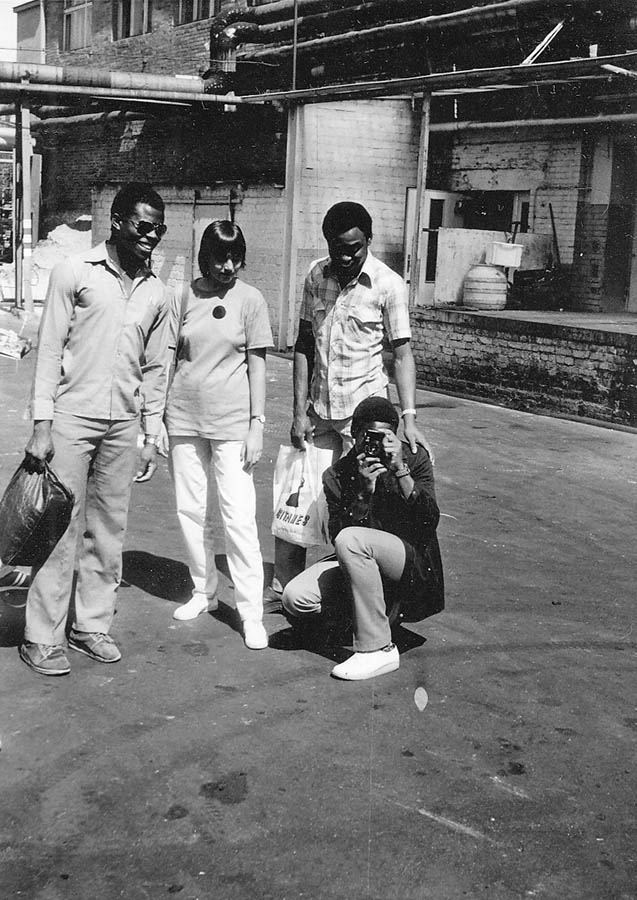

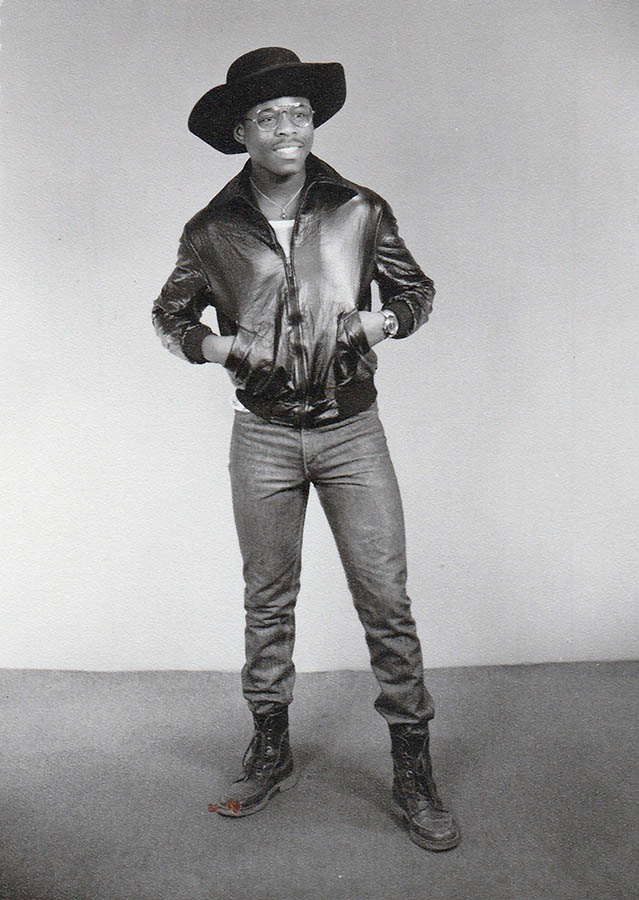

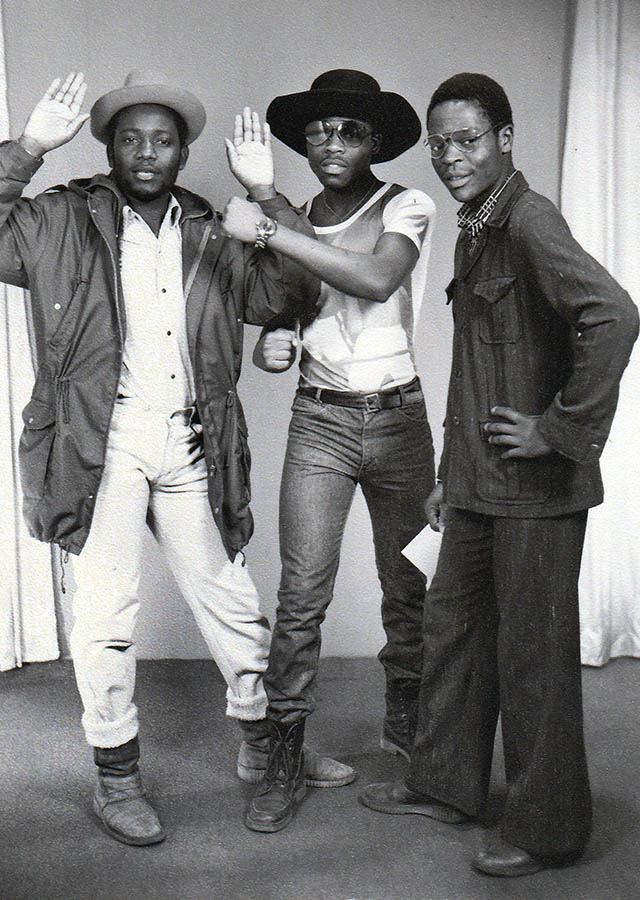

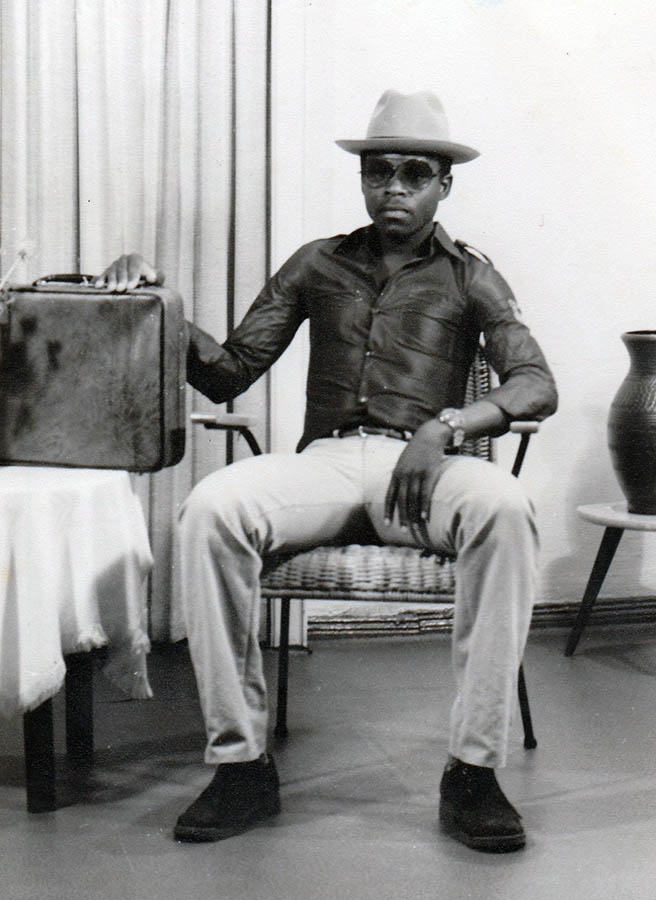

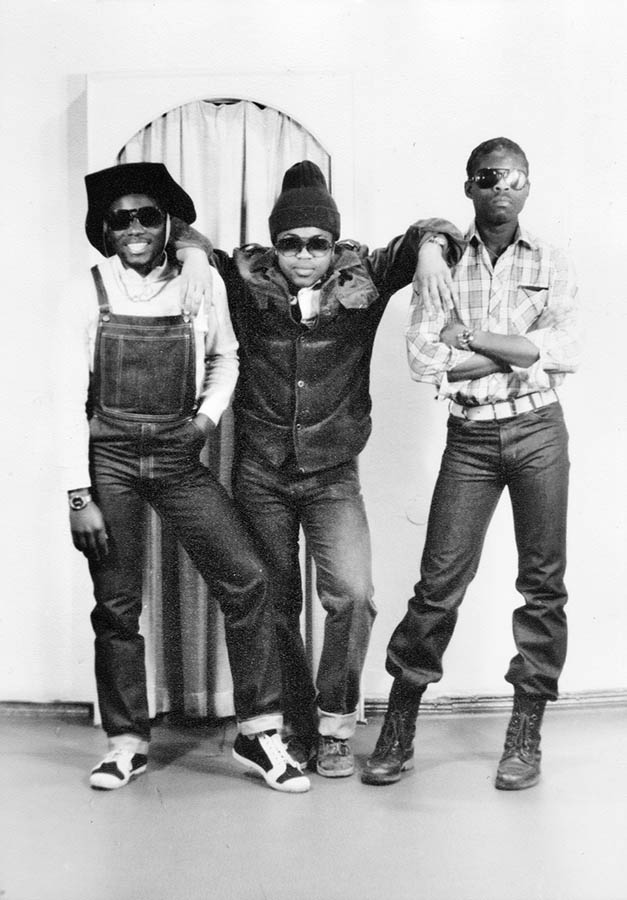

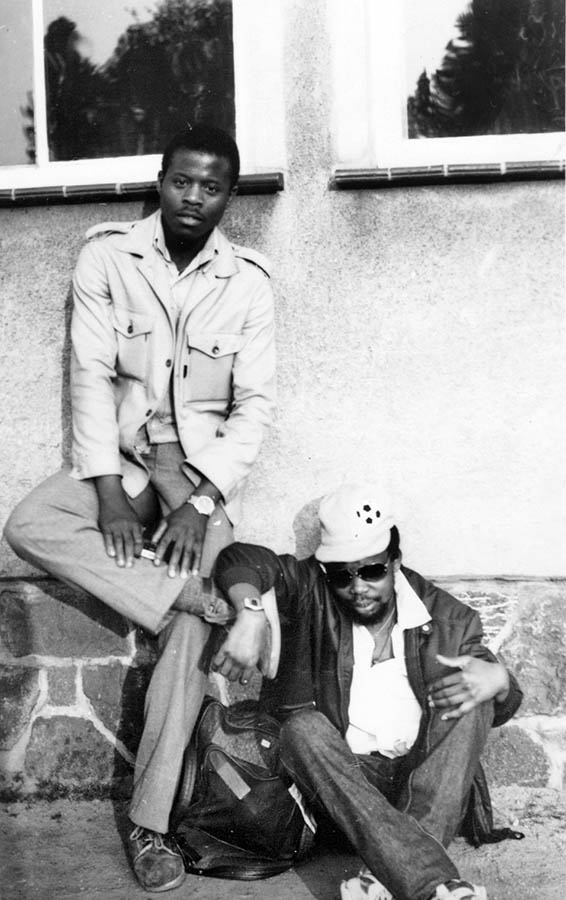

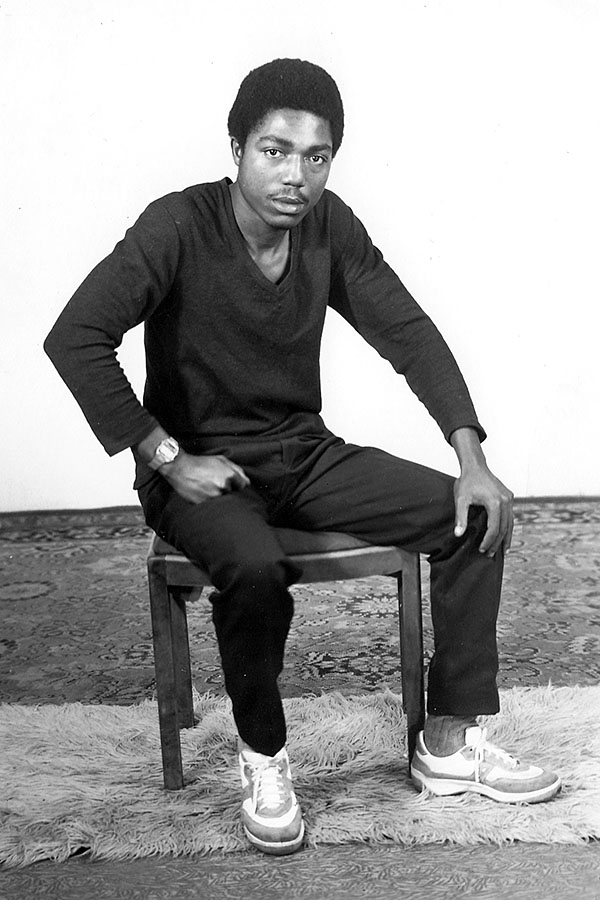

In the photo studio

Upon arrival, Ibraimo and his colleagues are given new outfits. Later Ibraimo gets fashionable clothes inspired by the cowboy movies he watched in Mozambique. Dressed like this, he heads to the photo studio together with friends. They send prints of the pictures to their families and friends. They shall see that they are doing well in faraway East Germany, that they are successful.

Out of the picture

The photos do not show the disillusionment after his arrival: the horror about having to work in a slaughterhouse, the disappointment about not being able to choose his training, the language difficulties. And that no consideration is given to the fact that Ibraimo does not eat pork.

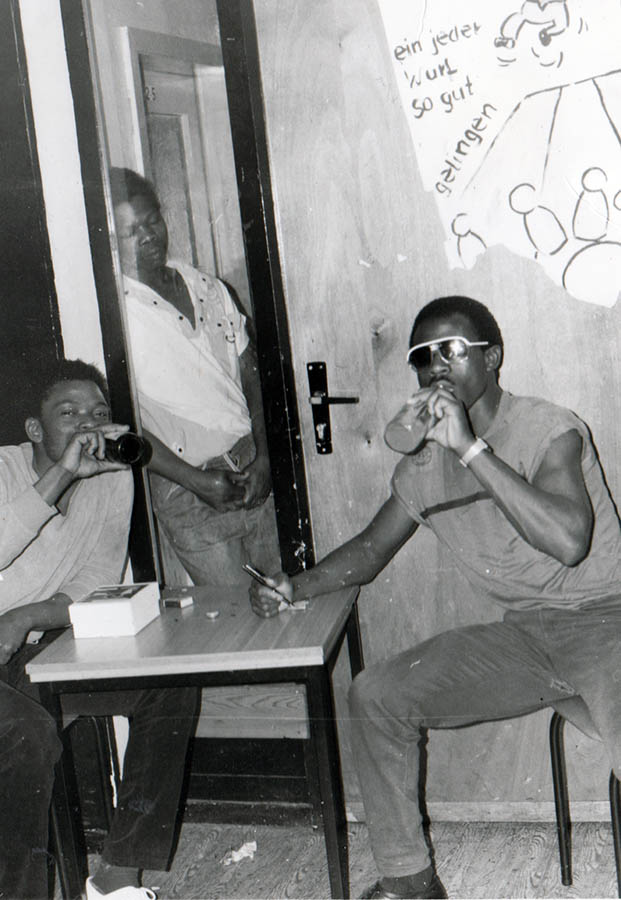

Meat packing

Ibraimo Alberto and some of his friends are assigned to train meat-processing in the VEB Fleischkombinat. At first, this sounds like modern technology to him, but the work is rather gross. Still, he is motivated and does his work well. In the second year of training, he is elected spokesman for the brigade. For his future in the GDR, however, his passion for sports becomes crucial.

We felt a bit like prisoners.

Ibraimo Alberto, Berlin 2022

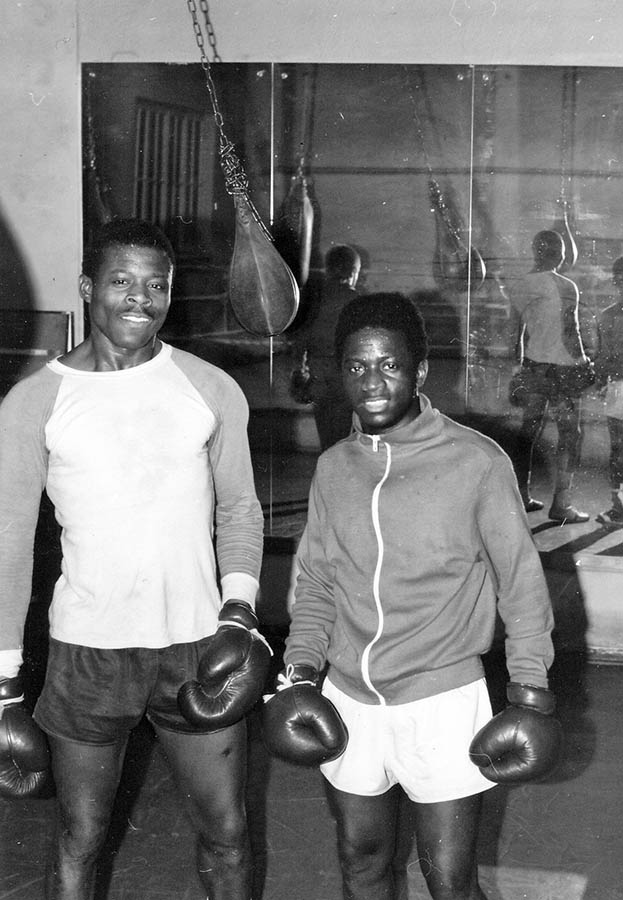

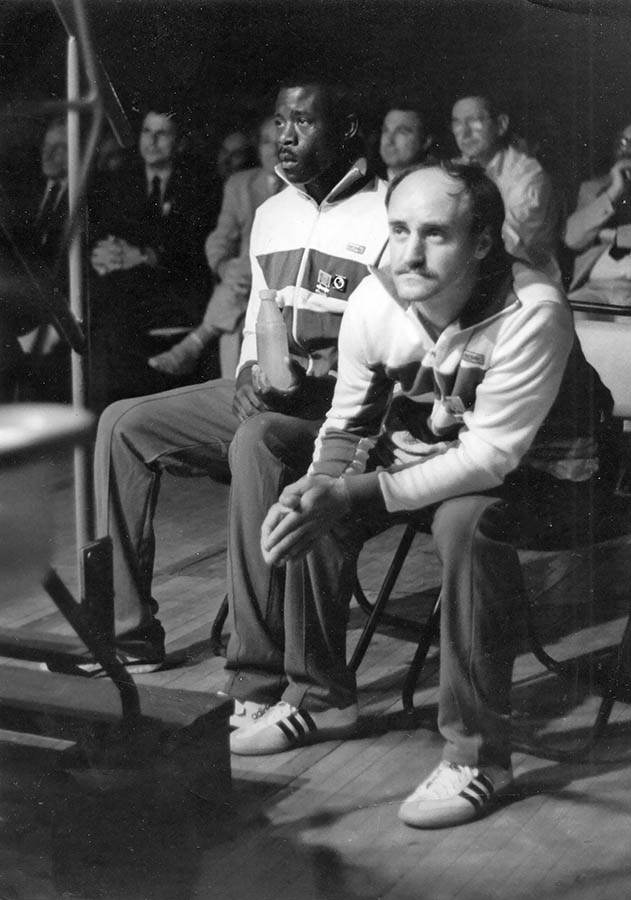

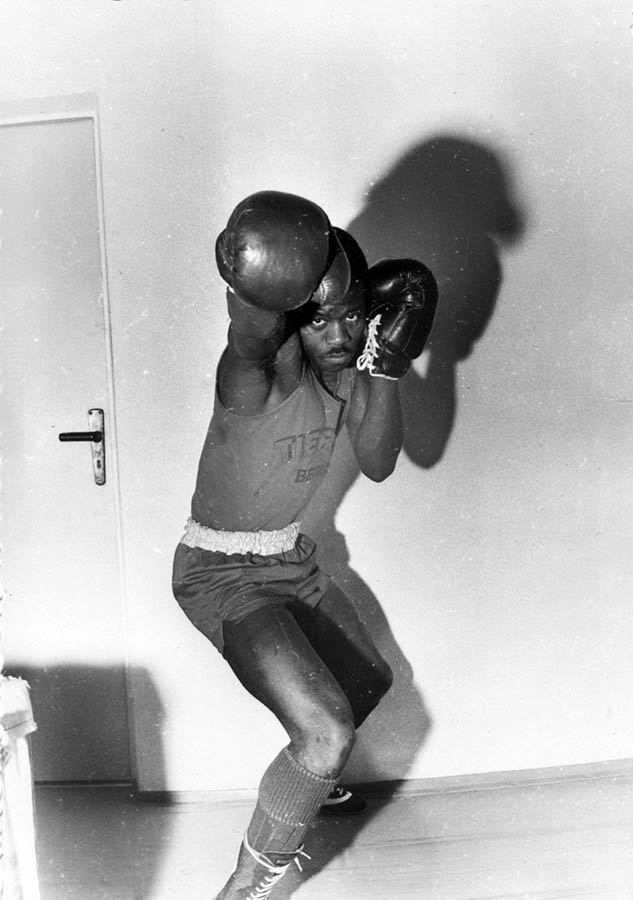

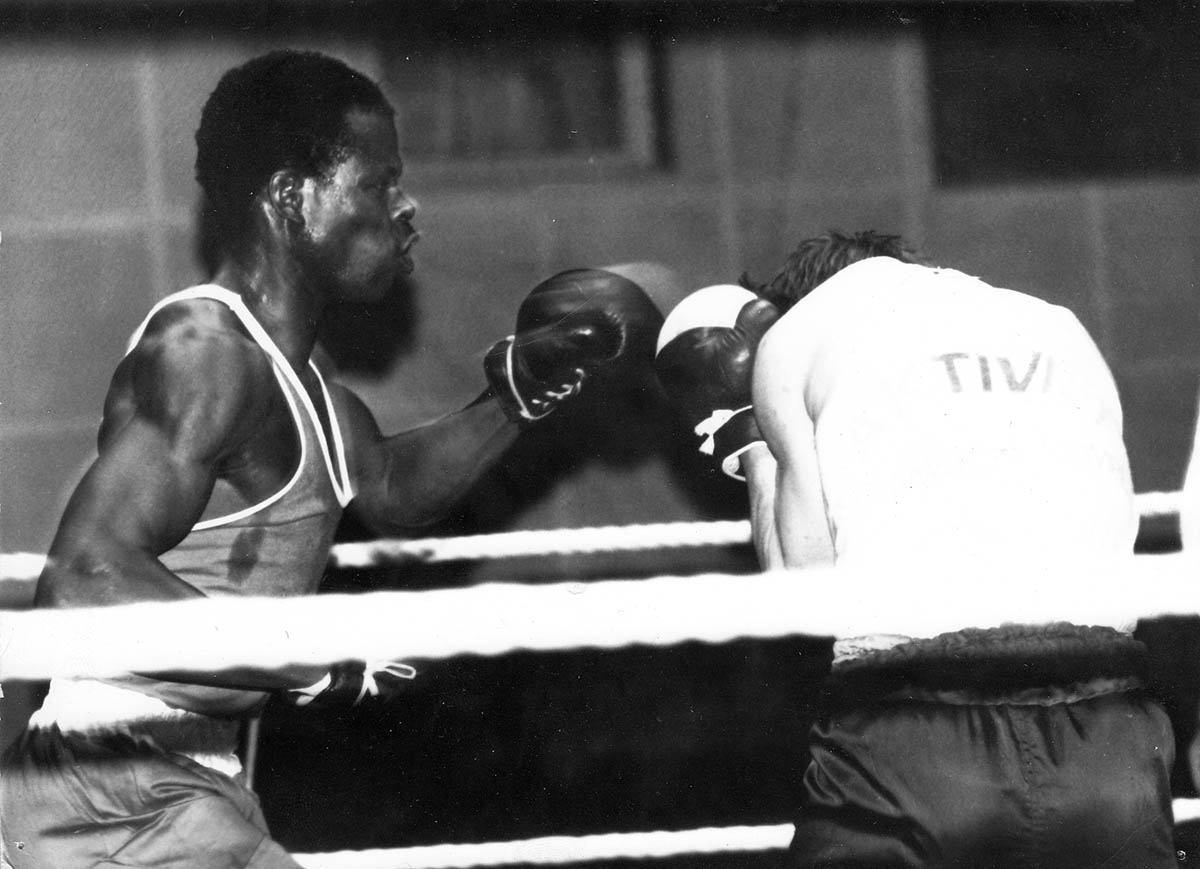

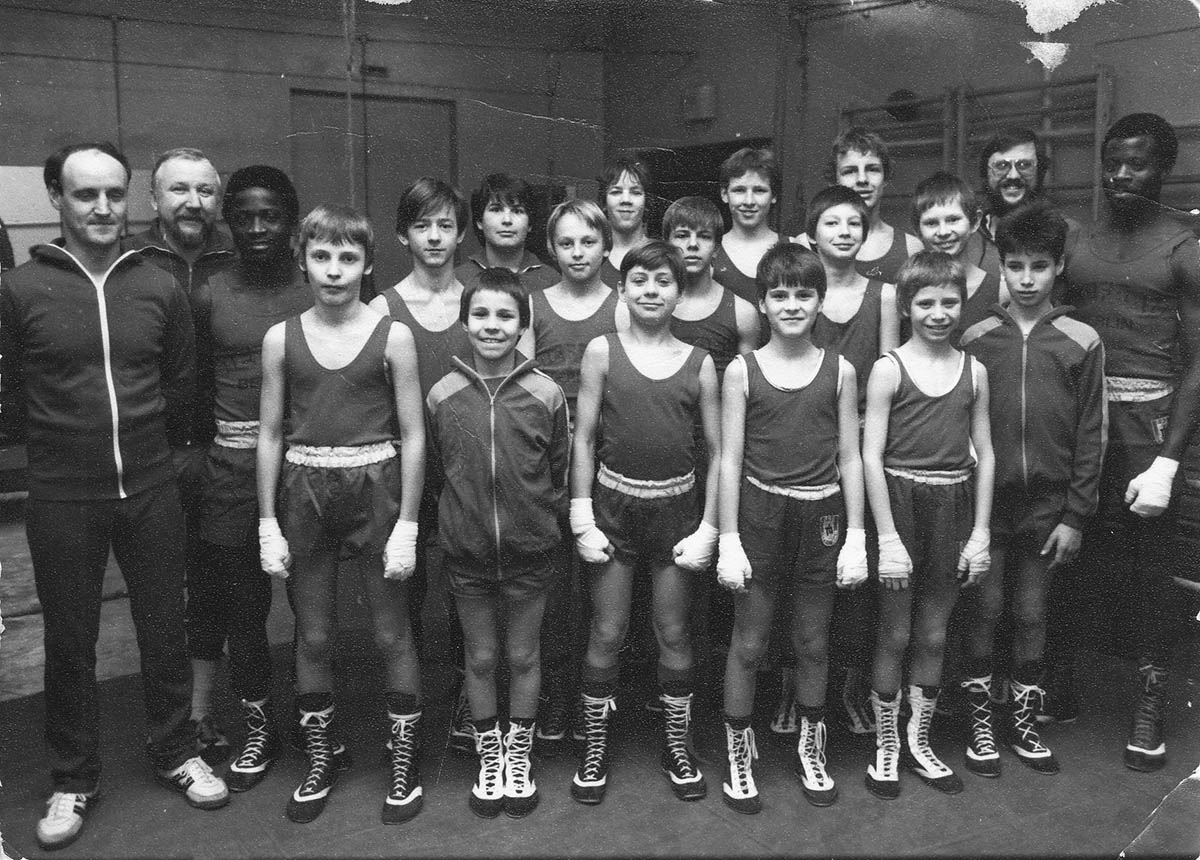

Boxing career

In the GDR Ibraimo Alberto wants to learn boxing. He approaches the very dedicated German teacher assigned to teach the Mozambican contract workers basic German skills in six months’ time. She puts him in touch with the VEB Tiefbau Berlin sports club. There Ibraimo starts his boxing training. Boxing means a lot to him, and not just from an athletic point of view: it helps him to stand up against racism. As a black boxer, he is frequently confronted with humiliating situations. Ibraimo takes part in competitions for his club throughout East Germany and abroad.

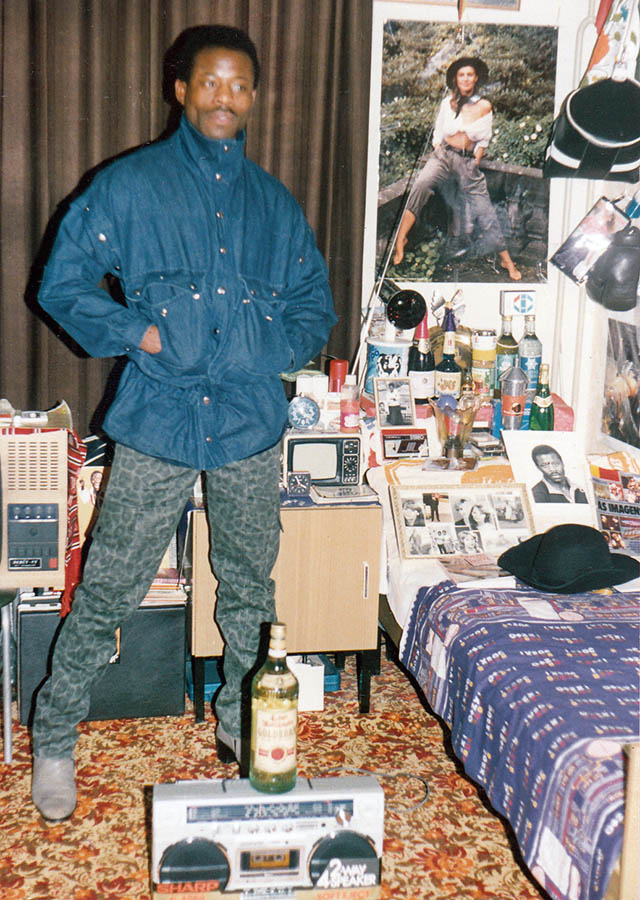

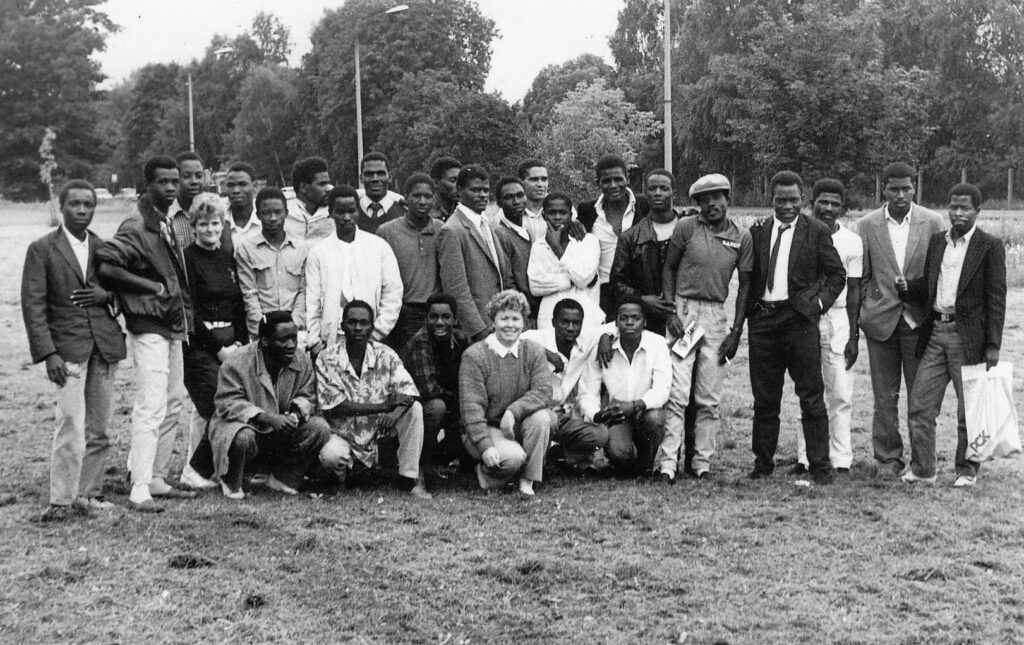

After work and the second contract

Not only for Ibraimo Alberto sport is an important leisure activity. Many of his Mozambican colleagues play soccer. Ibraimo manages and coaches a team of fellow residents/roommates. On weekends they organize discos in the residential home. Ibraimo has settled in. After his first contract expires, he shortly returns to Mozambique, before doing a second labor cycle in the GDR in 1986. He is assigned group leader for Mozambican contract workers in the VEB Stralau glassworks.

Structural and physical violence

Ibraimo Alberto’s assignment as group leader comes at a time when the contract workers are receiving less and less training. Their main task is to maintain the moribund industrial production. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 most Mozambicans, including Ibraimo, lose their jobs. They are urged to return prematurely to their countries of origin. Ibraimo stays. In 1990 he moves from Berlin to Schwedt, where he boxes for the Uckermärkische Boxverein Schwedt 1948 in the national league. At the same time, he trains as a social worker. His boxing career helps him survive the extreme racist violence of the 1990s. In Schwedt he volunteers as a city councilor and foreigners’ commissioner for several years. He and his family leave the city in 2011 after experiencing constant racist attacks.

Today he lives in Berlin and works with migrants and refugees.

Credits:

Jessica Massóchua conducted the interview in Berlin in 2021.

Text: Isabel Enzenbach

Research and research protocol photos: Jessica Massóchua