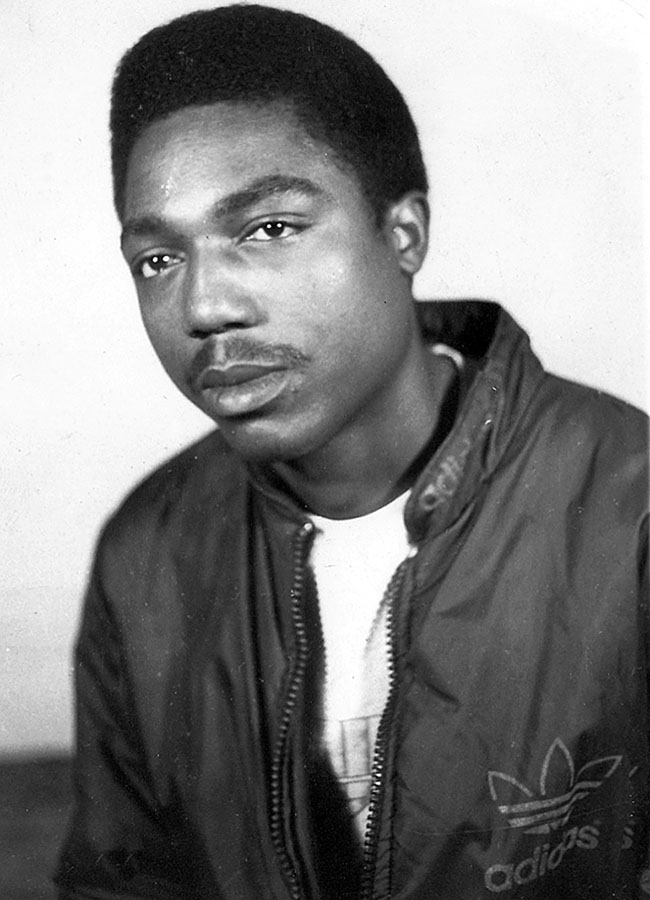

Augusto Jone Munjunga

Augusto Jone Munjunga works as a financial trader in Angola. By coming to the GDR he wants to qualify for university. That is why he signs on as a contract worker to East Germany in 1987. He is sent to the slaughter and meat processing combine, Schlacht- und Verarbeitungskombinat, in Eberswalde. In 1990 his friend Amadeu Antonio is murdered there by a racist mob of young men. Jone stays in Eberswalde. He does not abandon the city to racists and fascists.

At the slaughterhouse

Augusto Jone Munjunga has trained as a financial clerk and works in an Angolan ministry. Since its independence from Portugal in 1975, Angola has been in a state of civil war[1].

The country lacks well-trained specialists, Angolans with international experience. Jone wants to advance his education and qualify for a university degree. The move to the GDR seems to be the right step into this direction. Moreover he hopes to leave behind the war in Angola. Arriving at the workplace in Eberswalde comes as a shock: a gigantic slaughterhouse, not a place, where he can learn anything meaningful. But there is no way out. Immediately at the airport, the 103 Angolans coming to work in Eberswalde have their passports taken away. First they get a three-month crash course in German, then work starts in three shifts.

Later we said that this is modern slavery.

Augusto Jone Munjunga, Eberswalde 2022

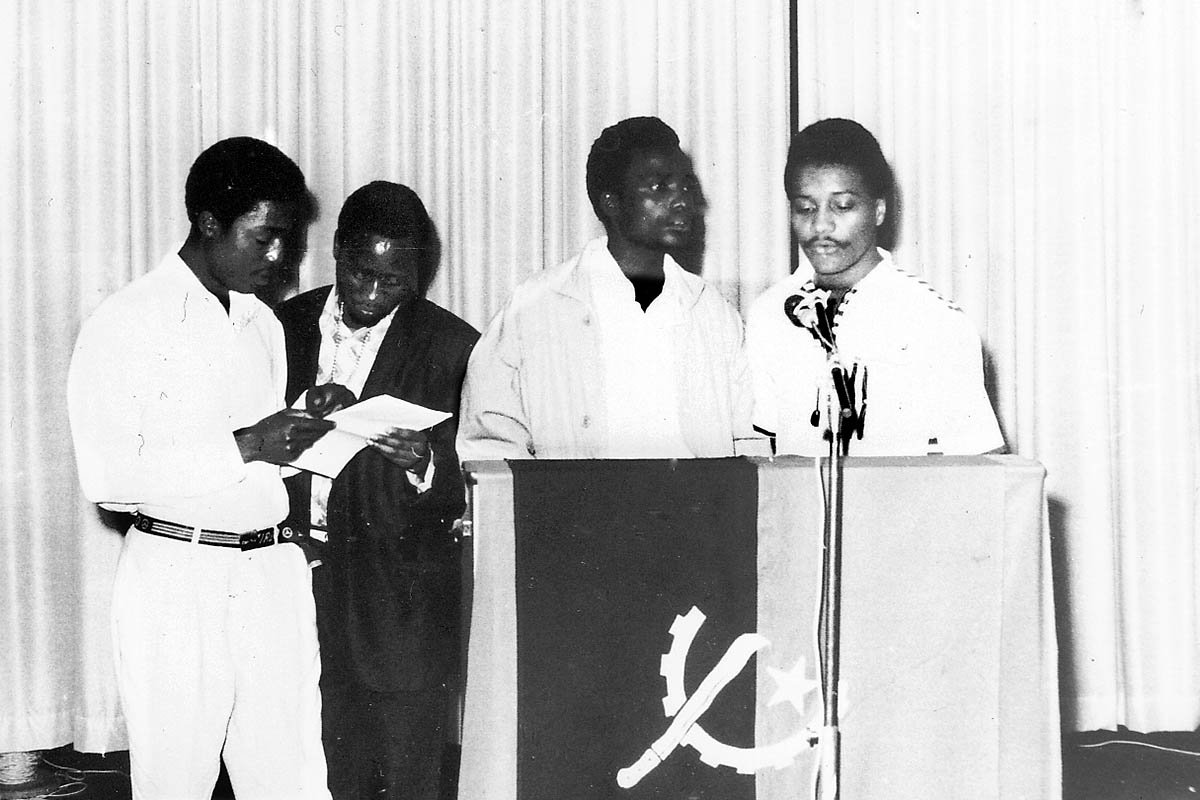

Committed and responsible

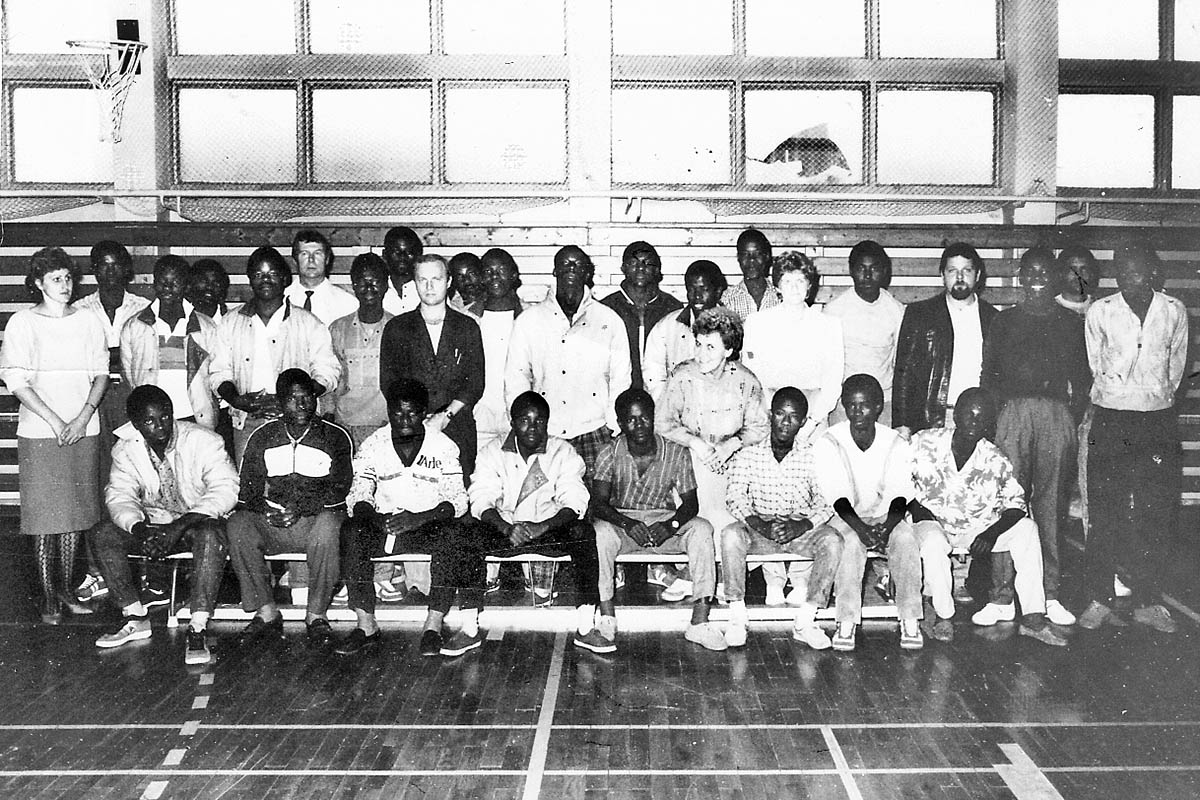

Augusto Jone Munjunga is chosen as the spokesman for his group. He mediates when problems arise, takes care of leisure activities, establishes contacts with the FDJ [2]. Soon he finds out who supports them in Eberswalde, with whom things are difficult. The young men have a particularly good relationship with the owner of the photo studio, which they soon visit to send photos home. The group fields a soccer and a basketball team, plus Jone and his colleagues start a band. “People didn’t know what reggae was and how to dance to it. That is what we played. But we also imitated East German music.” Occasionally the plant organizes excursions, for instance to Sachsenhausen Memorial.

Striking for better wages

There are three companies in Eberswalde that employ contract workers. In the 1980s these are people from Algeria, Angola, Cuba, Mozambique and Vietnam. Most of them live in three residential homes, where they are housed according to their countries of origin. The Angolans are the last group to arrive in the city. They buy clothes with the logos of Western brands from Polish workers. When the Angolan workers learn that they are not paid even half as much as their Polish colleagues for the same work, they retaliate with a strike. Yet this is quickly quashed. As a result, some Angolans are promptly deported to Angola. The others guess that at home they will be drafted for military service as a punishment. This intimidates the group, because they are all aware that this deployment can prove fatal.

Augusto Jone Munjunga talks about striking for equal pay and equal work.

We were isolated.

Augusto Jone Munjunga, Eberswalde 2022

Discipline does (not) pay out

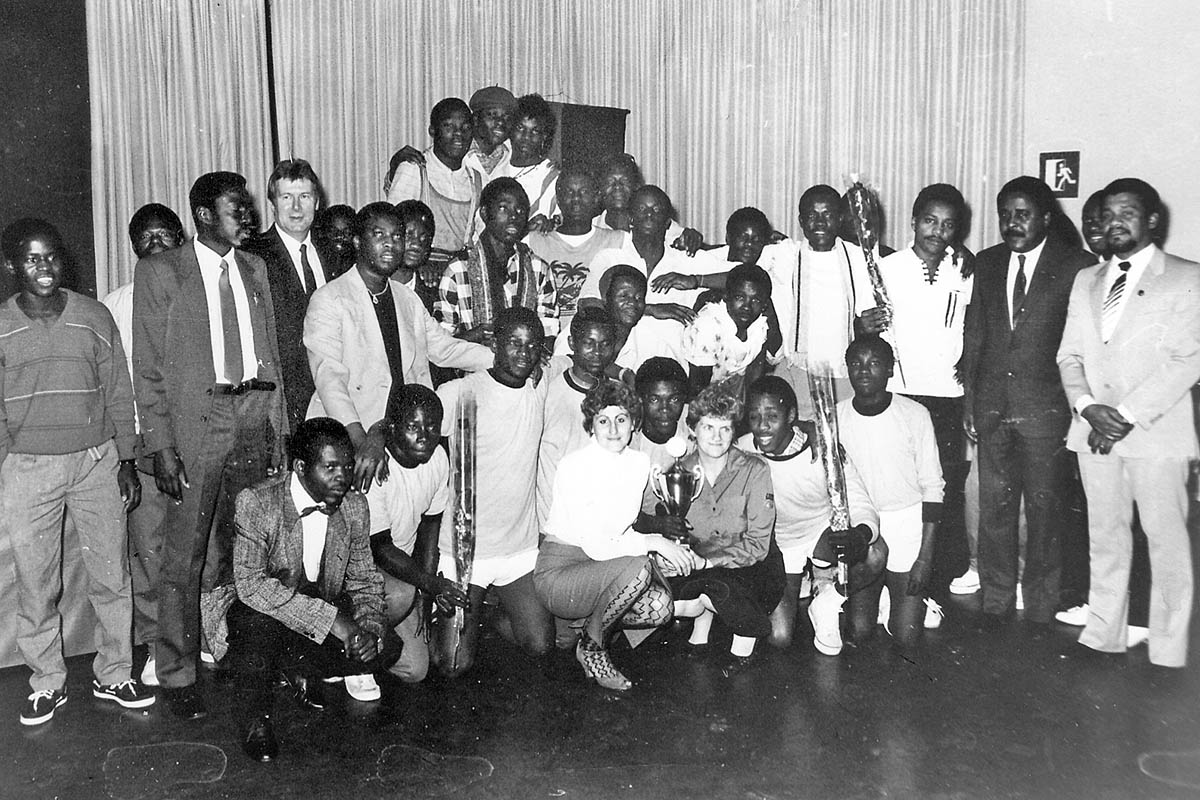

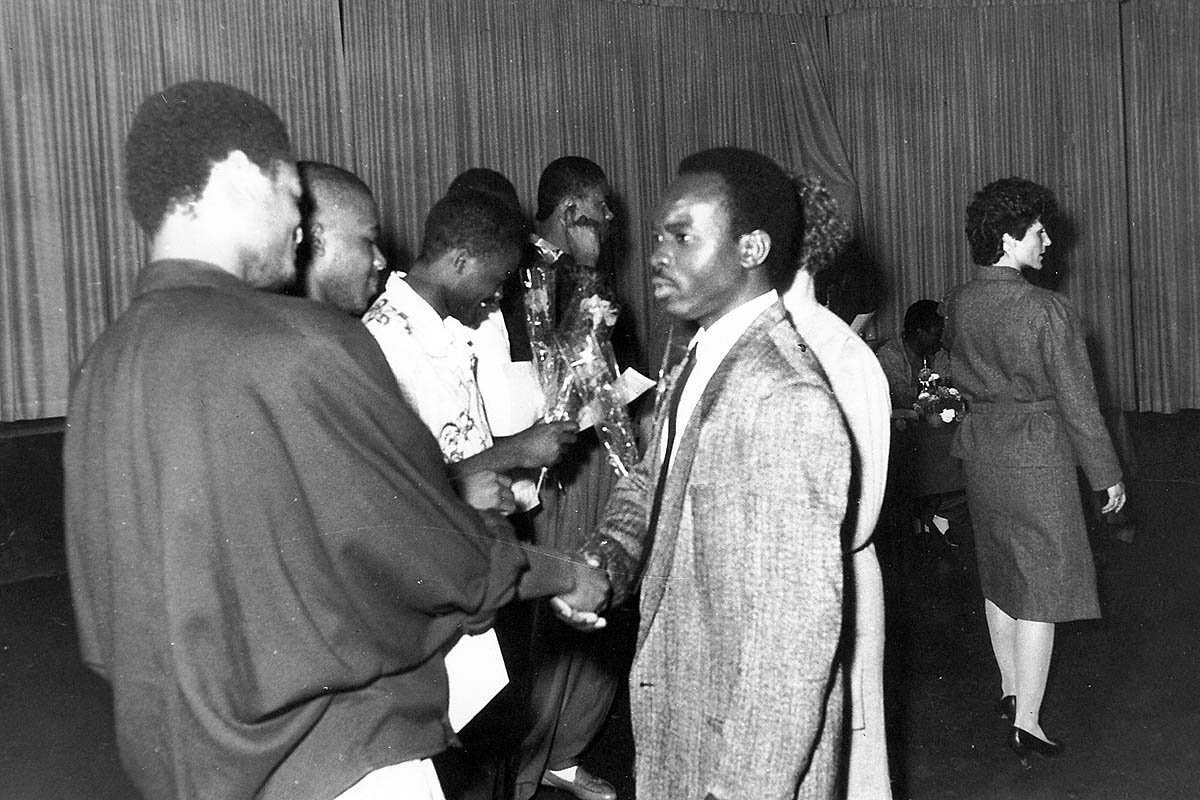

After the strike leaders have been deported, awards are given to those who work particularly disciplined. At plant festivities, certificates and flowers are handed out. Likewise representatives of the Angolan embassy pay attention to maintaining discipline. The structural problem remains untouched: The promised qualification does not happen.

Ignored/Excluded after Work

The contract workers working in Eberswalde are housed in Finow in the three residential blocks of the large plants. “The first block, the blue one, housed Germans and Poles, the red block in the middle was from our slaughterhouse, there were Angolans and Germans, and in the brown block next to it lived Germans, Vietnamese and Mozambicans,” says Augusto Jone Munjunga. The Angolans run a disco in their basement, and the residents of the blocks meet there. But they are isolated from social life in Eberswalde. Many of the colleagues they work with during their shifts ignore them after work.

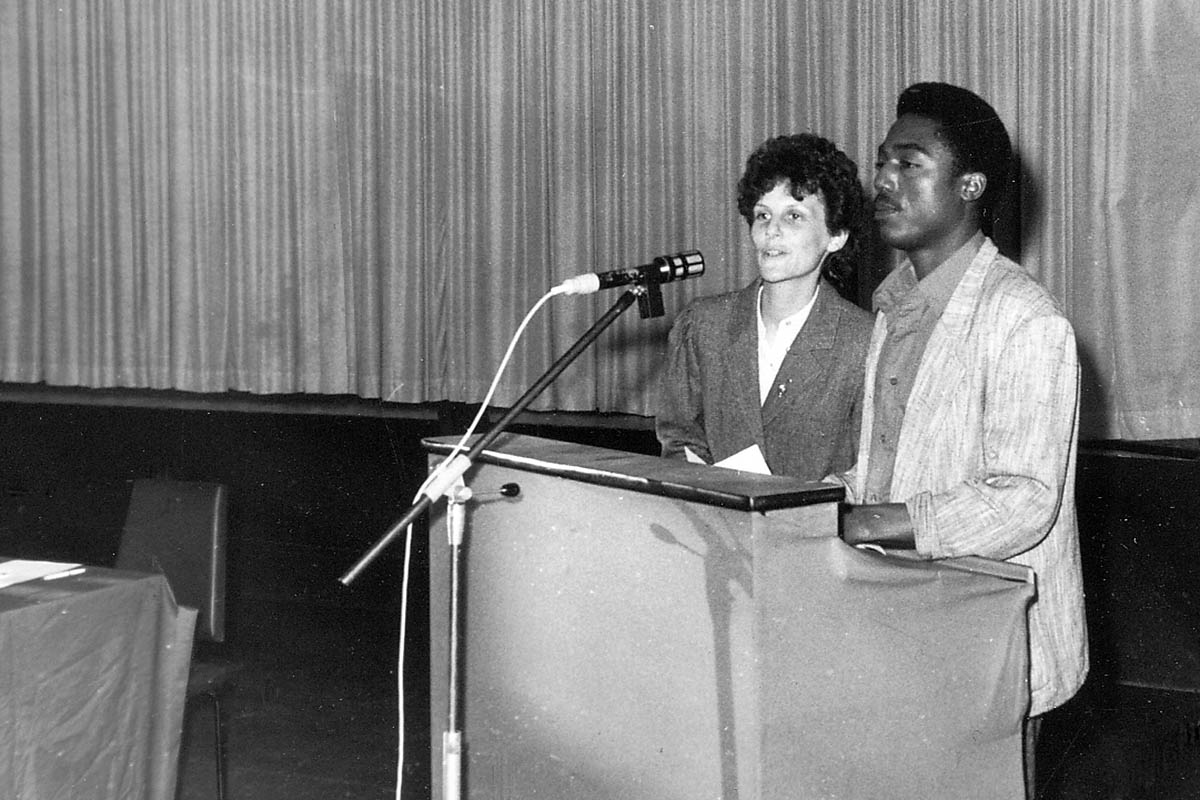

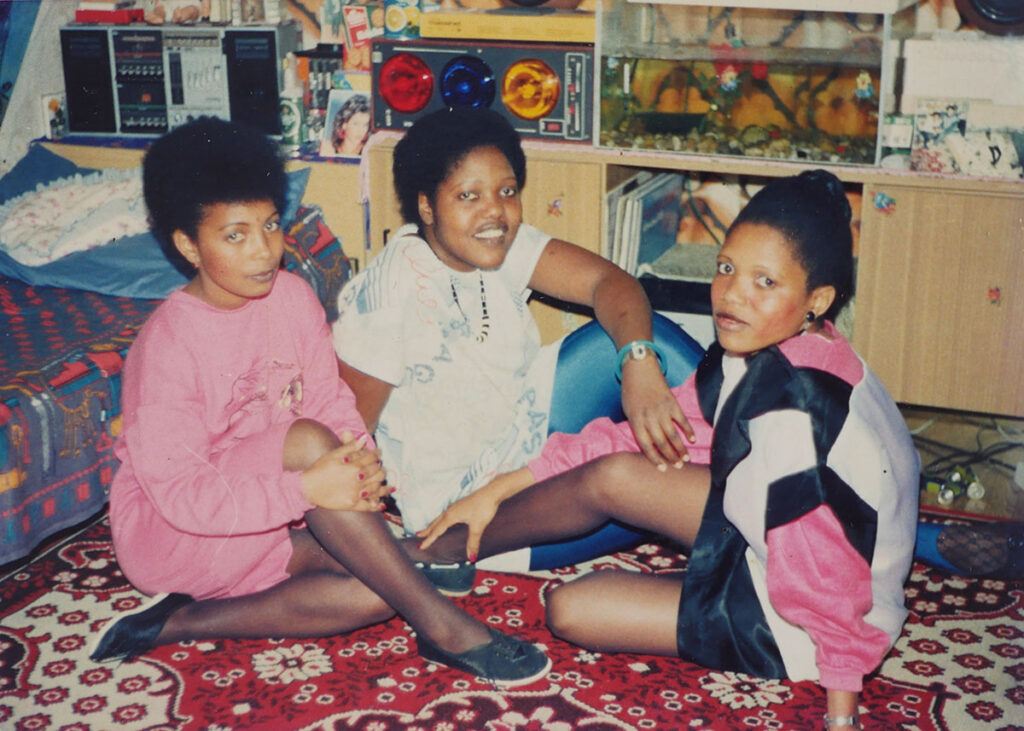

Amateur photographers at work

Jone buys a camera and contacts Christian Fenger, an amateur photographer. He works at VEB Walzwerk in Eberswalde and is active in the plant’s photo circle. The photo circle receives money from the plant for photographic materials, and serves a meeting place for those who take ambitious photographs, it also organizes its own photo exhibitions. Christian Fenger sets up his own darkroom in the Mozambicans’ dormitory. He provides advice on photography and takes many pictures of them.

Augusto Jone Munjunga describes everyday life and everyday racism and how he himself started with photography.

Assassination of Amadeu Antonio

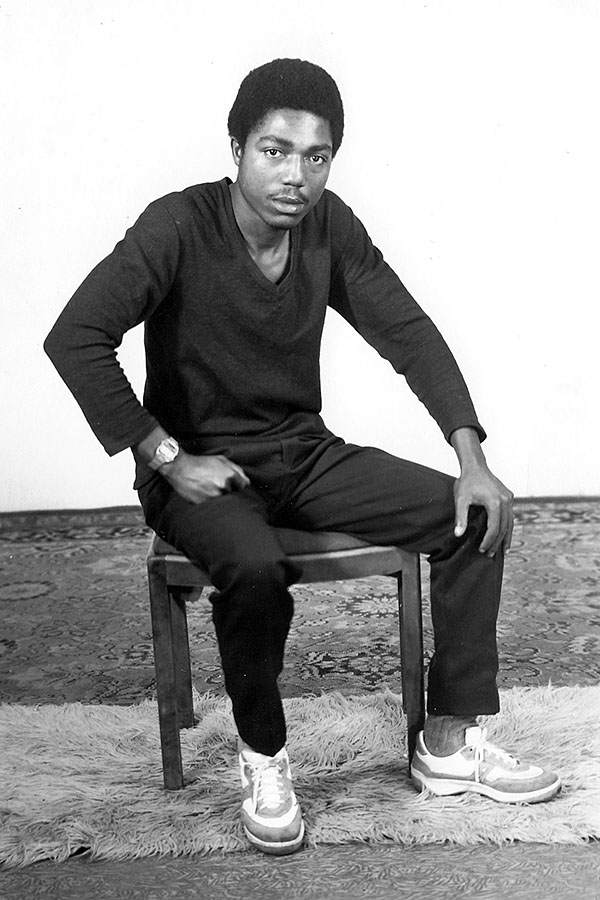

The picture that Augusto Jone Munjunga has taken of his friend Amadeu Antonio goes around the world. Amadeu Antonio is Jone’s friend and colleague; he, too, is employed as an Angolan contract worker in the slaughterhouse. Jone takes the photo that shows Amadeu as a cheerful young man on his motorcycle. On November 24, 1990, after visiting a local pub, he is beaten and kicked to death by a group of racist, right-wing extremist men. Amadeu Antonio is one of the first fatalities of the so-called Baseballschlägerjahre (Baseball Bat Years), the period in the 1990s when far-right racist hate crimes were ubiquitous in several places.

This is the beautiful German country after the fall of the Wall.

Augusto Jone Munjunga, Eberswalde 2022

In mortal fear

After the fall of the Wall, Eberswalde becomes a right-wing extremist hotspot, a place where racist violence is constantly present, even in the supermarket. Jone describes everyday life: “You take your shopping, go to the checkout to pay. And people walk away. So you let the Germans go first. Maybe it is your turn at the end. Or maybe they say ›no, we don’t serve you‹, then you must leave everything. What are you supposed to do then? Nothing at all.”

The contract workers live in constant fear. “Going out on the street, alone, was suicide for us. Visiting a restaurant or going to a pub, even worse, you really couldn’t go there. Those were the 1990s for us. It is also the period in which our children were born.”

This time for me, it was war.

Augusto Jone Munjunga, Eberswalde 2022

Hostile Structures – Self Organization

With the German reunification, the legal and social situation of the Angolan contract workers aggravates even more. The German government terminates the bilateral agreements. Many contract workers lose their jobs, and hence their residential accommodation and residence permits are no longer available. In this situation of disenfranchisement, many see no alternative but to return to Angola. There the civil war continues to define life. Augusto Jone Munjunga remains in Eberswalde. In 1994 he establishes the Palanca association as a meeting place, source of information and shelter in Eberswalde.

Augusto Jone Munjunga lives in Berlin and Eberswalde and works as a social worker.

Credits:

Jessica Massóchua conducted the interview in Eberswalde in 2022.

Text: Isabel Enzenbach

Research and research protocol photos:Jessica Massóchua

Video edting concept: Julia Oelkers