Yolanda Cuesta Osloal

In 1978, at the age of twenty, Yolanda Cuesta arrives from Havana in Leipzig. At first she is disappointed, because she wanted to study and not work in the factory. But then she adapts to her life in the GDR.

The GDR as a sanctuary

Yolanda Cuesta is active in the youth organization of the Communist Party of Cuba. She wants to become an English teacher and trains as such. One day on her way home from school, she is sexually attacked. The attack leaves her traumatized, she hardly speaks any more. Medication helps her to cope with everyday life. Her mother and a friend are convinced that it would be best for Yolanda to leave Cuba for a while. When they hear about the agreement reached between Cuba and the GDR in 1978 on Qualification in Simultaneous Employment (Qualifizierung bei gleichzeitiger Beschäftigung), they support Yolanda’s application. She is selected as an activist of the youth organization. After a two-month language and preparation course in Cuba, the journey begins for fifty young Cubans, straight from the training camp to the airport. Supposedly thus making it easier for them to bid their families goodbye.

Reception in Leipzig

The reception in Leipzig is friendly. Yolanda Cuesta recounts a kind building manager welcoming the group and showing them around the residential home. Yolanda likes it: “It was a good building, built for students and workers. A flat for four people. We had two rooms, two people per room, plus living room, bathroom, kitchen. I thought: Well, at least I’m comfortable. The only problem was the cold.” The next day, the administrator explains German customs to them, the do’s and don’ts. Her words come as a shock to the young Cubans.

As you know, Cuban girls put curlers in their hair and go out like that. But not here!

Yolanda Cuesta Osloal, Havana 2021

She warns the Cubans not—under no circumstances!—to go out on the street with curlers. She also points out that picking flowers is punishable by a fine. Yolanda Cuesta is one of the four women in the group. She moves into a flat with a friend and two young men. One of them, Lazaro, later becomes her husband.

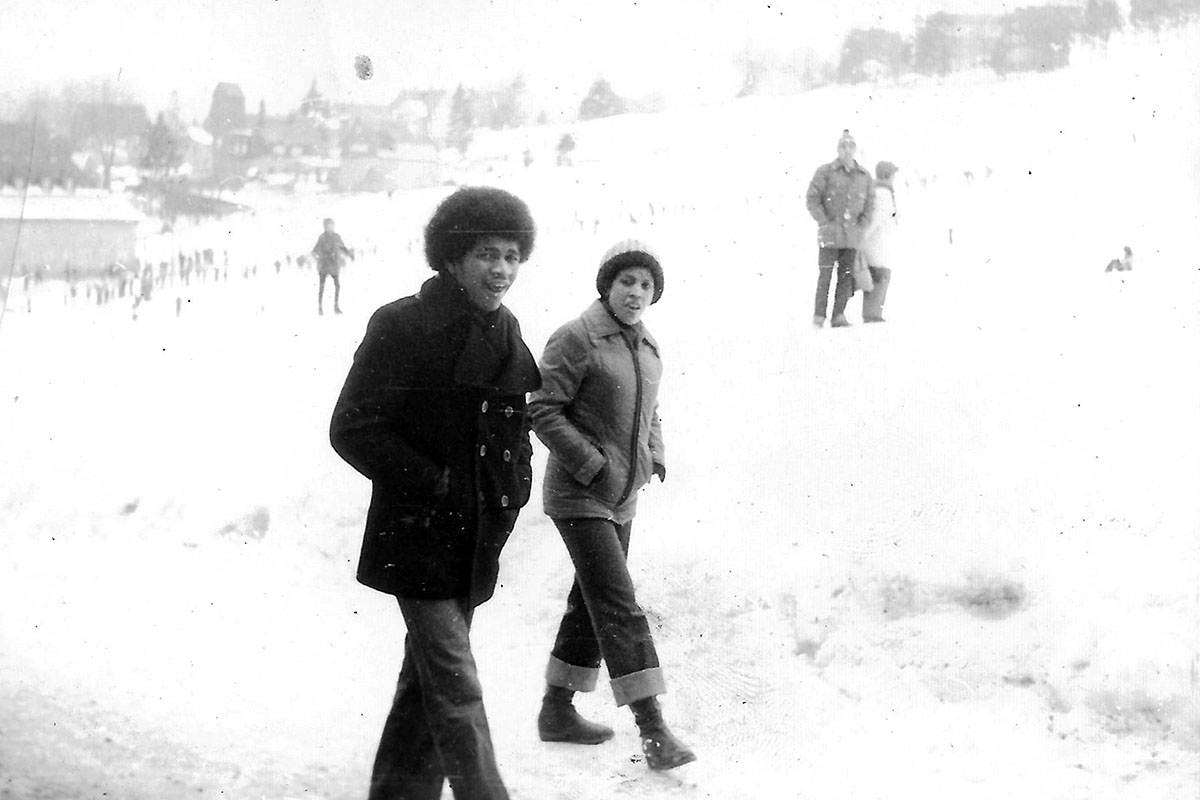

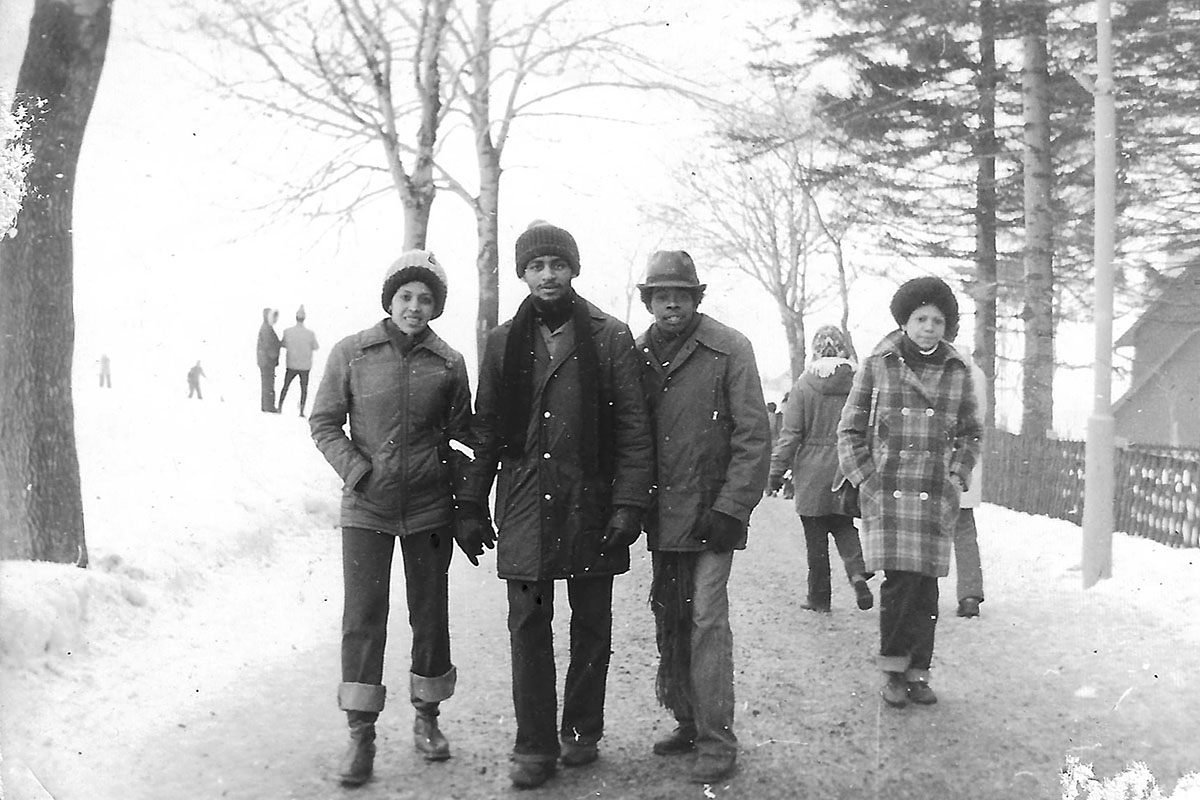

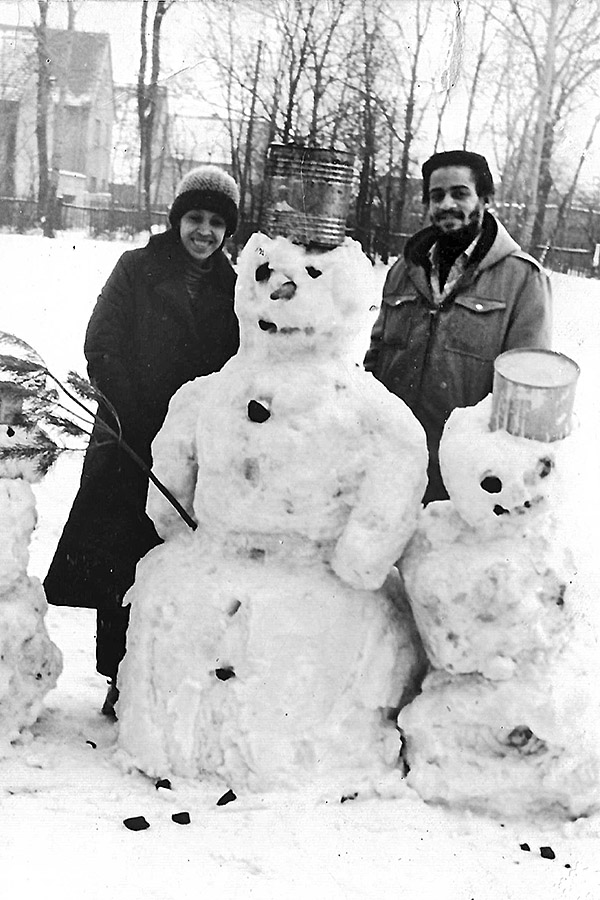

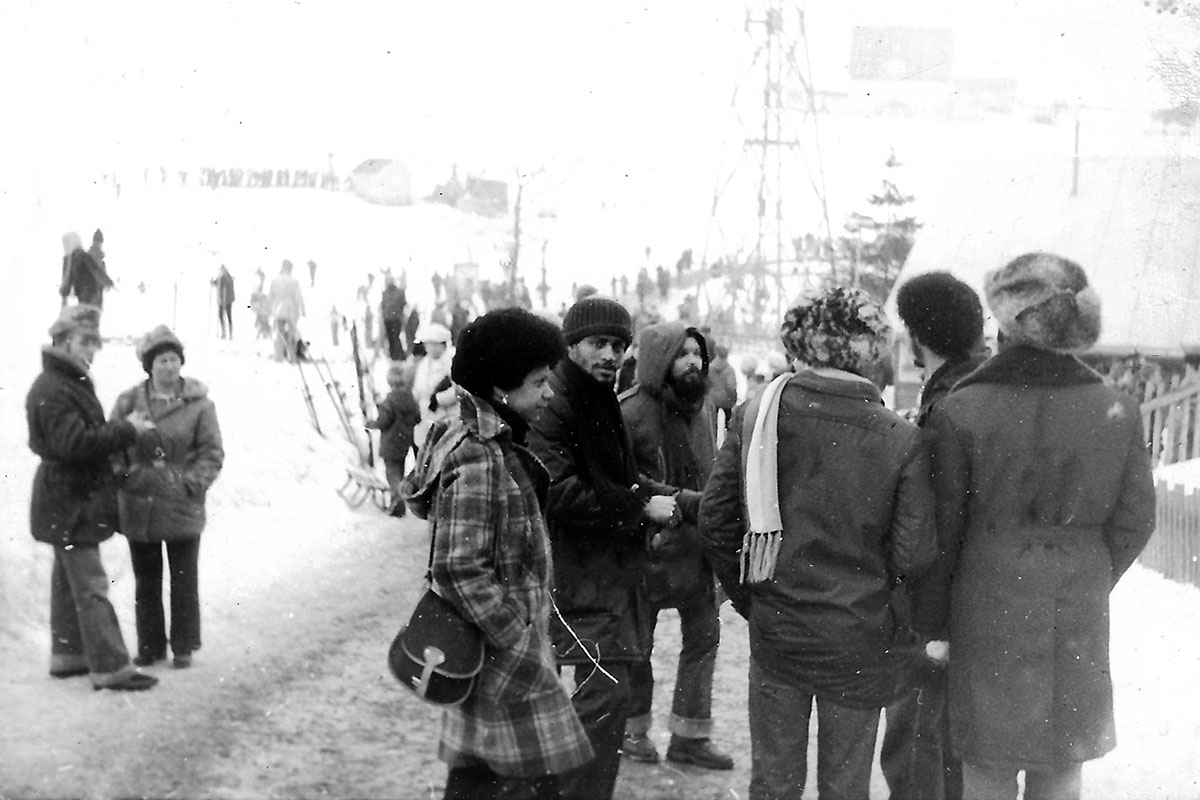

The snow disaster of 1978/79

Yolanda Cuesta belongs to the first group of young Cubans that arrived in the GDR as contract workers under the bilateral government agreement of 1978. They get caught up in the disastrous winter of 1978/79 in Leipzig, where temperatures drop to minus twenty degrees Celsius and the energy supply collapses. For days on end electricity and heating are out. Yolanda and her flat mates shove their beds together, huddle under all the blankets they can find, light candles, convinced that they are going to freeze to death. Later they enjoy trips to ski resorts. Yolanda remembers well the cold, the snow and the many layers of thick clothing, but not the place names.

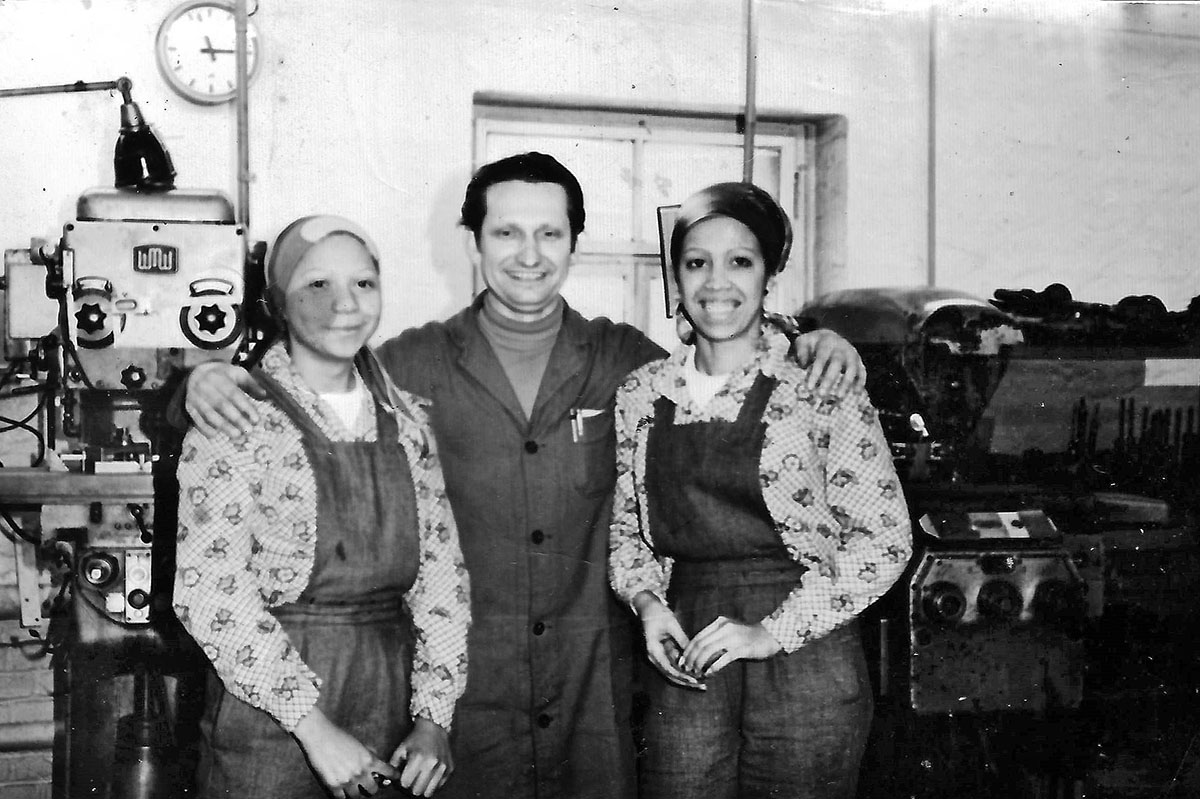

Cutting metal instead of studying chemistry

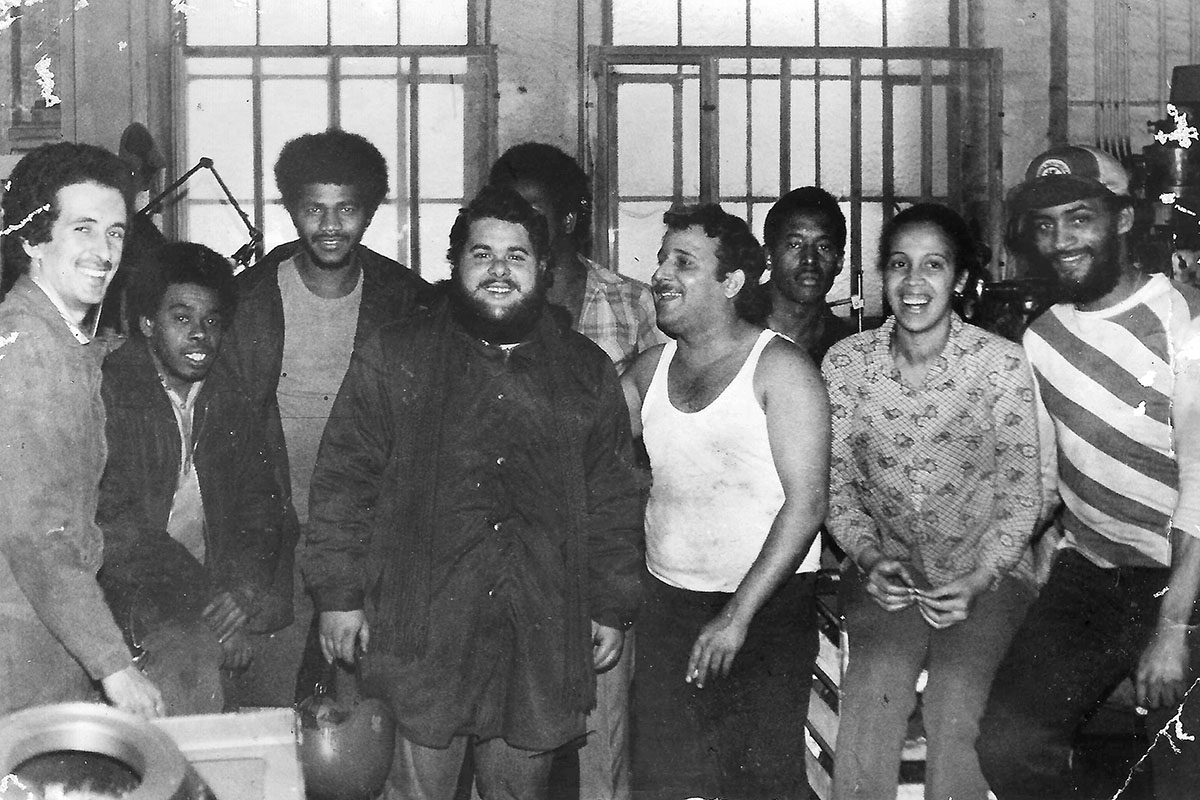

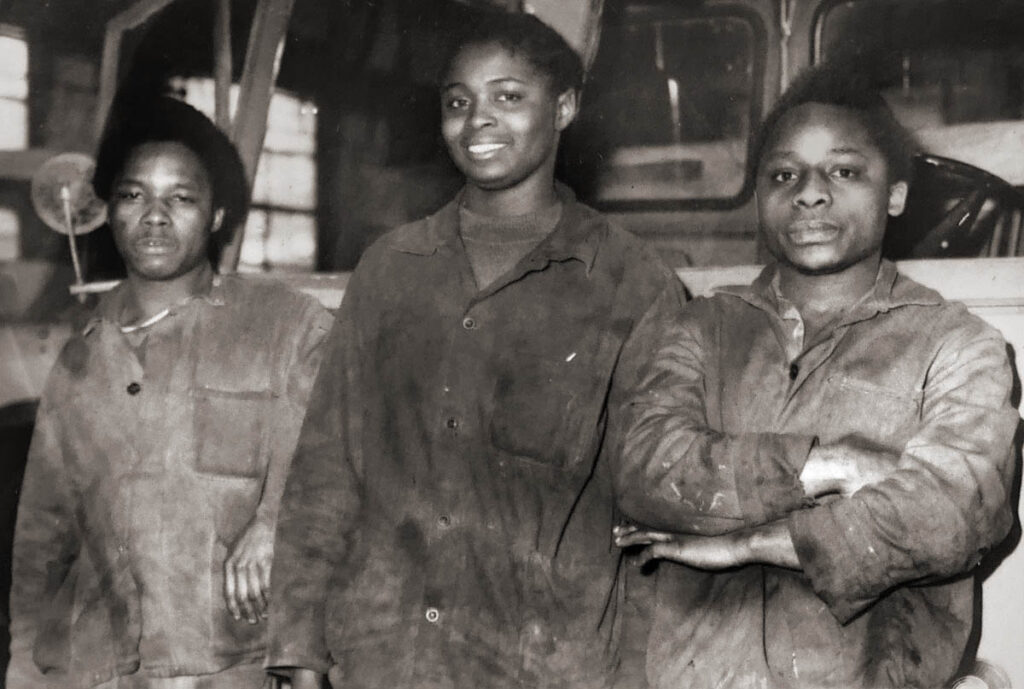

Yolanda Cuesta’s group works in the VEB “Joliot Curie” Fahrzeuggetriebewerke (Vehicle Transmission Plant) Leipzig. “First I was a bit irritated because basically I wanted to study industrial chemistry. But when we got there we were supposed to become skilled metal cutters.[1] That was what was needed most. And that actually annoyed me a bit. So we arrived at the factory and it was, well, so-so. But when we started working, we met people who were really good. They helped us a lot. So we settled in more and more.”

Working for/Serving two states

The stay of the young Cubans has two objectives, one is to alleviate the labor shortage in the GDR, and the other to help Cuba in training skilled workers for industrial professions. Yolanda Cuesta explains: “What did Cuba need? Machines and all that. What did we do? We helped with our workforce. They took a percentage of what we earned and bought machines and things like that. We supported them with what they didn’t have, the hand of labor.” The deducted percentage equaled 60 per cent of the wage exceeding the 350 marks needed as basics for living expenses. Following her initial frustration, Yolanda comes to terms her work.

... and in a jiffy the spare part was ready and landed in a box. Bam! I liked it because you could see the result of your work. You were the one who turned unworked iron into a spare part.

Yolanda Cuesta Osloal, Havana 2021

Positive Memory

Yolanda Cuesta perceives the VEB “Joliot Curie” Fahrzeuggetriebewerke as a modern factory — compared to Cuba. She is impressed by the equipment and the variety of machines. She is ambitious, works on different machines, solves emerging problems in the factory and is proud to manage on her own as a woman. She is self-assured about her work and believes in the vision that she and her colleagues will be able to put the skills they acquire in the GDR to good use in Cuba. “We were young, we were courageous. More than that! Wow …, because if you look at our age then …” she emphasizes.

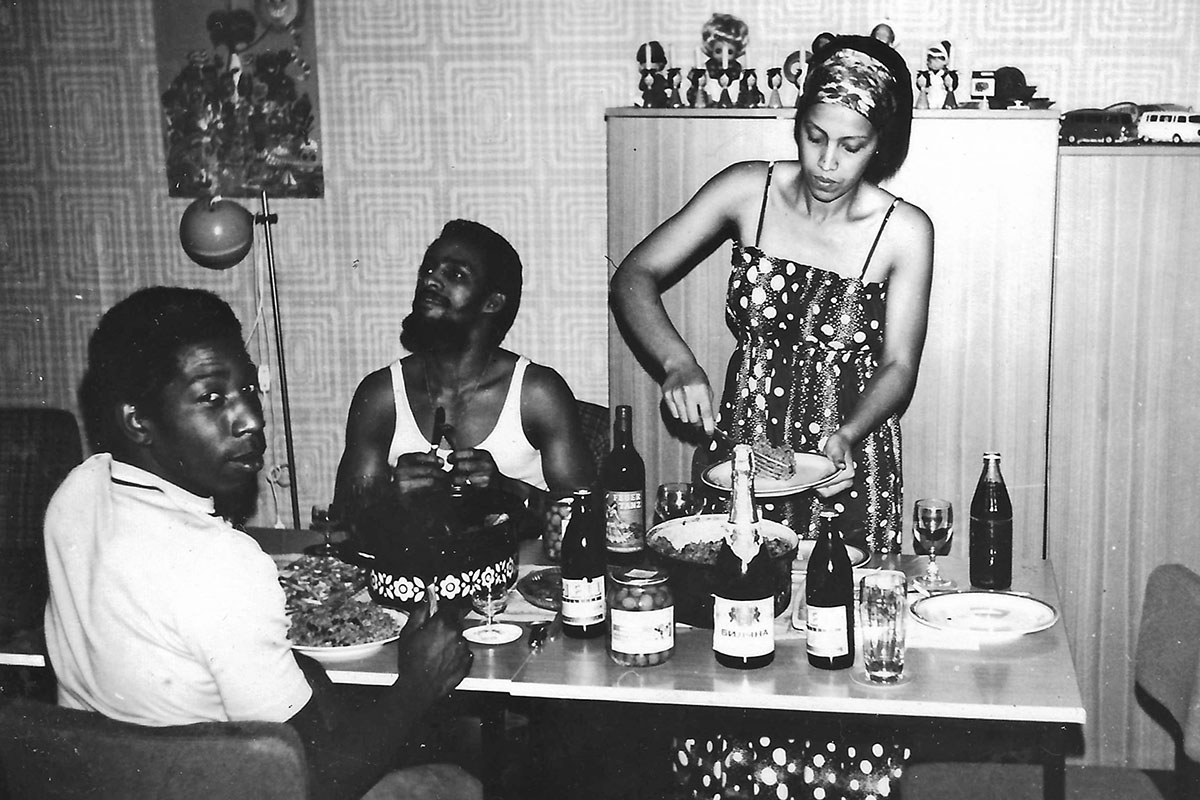

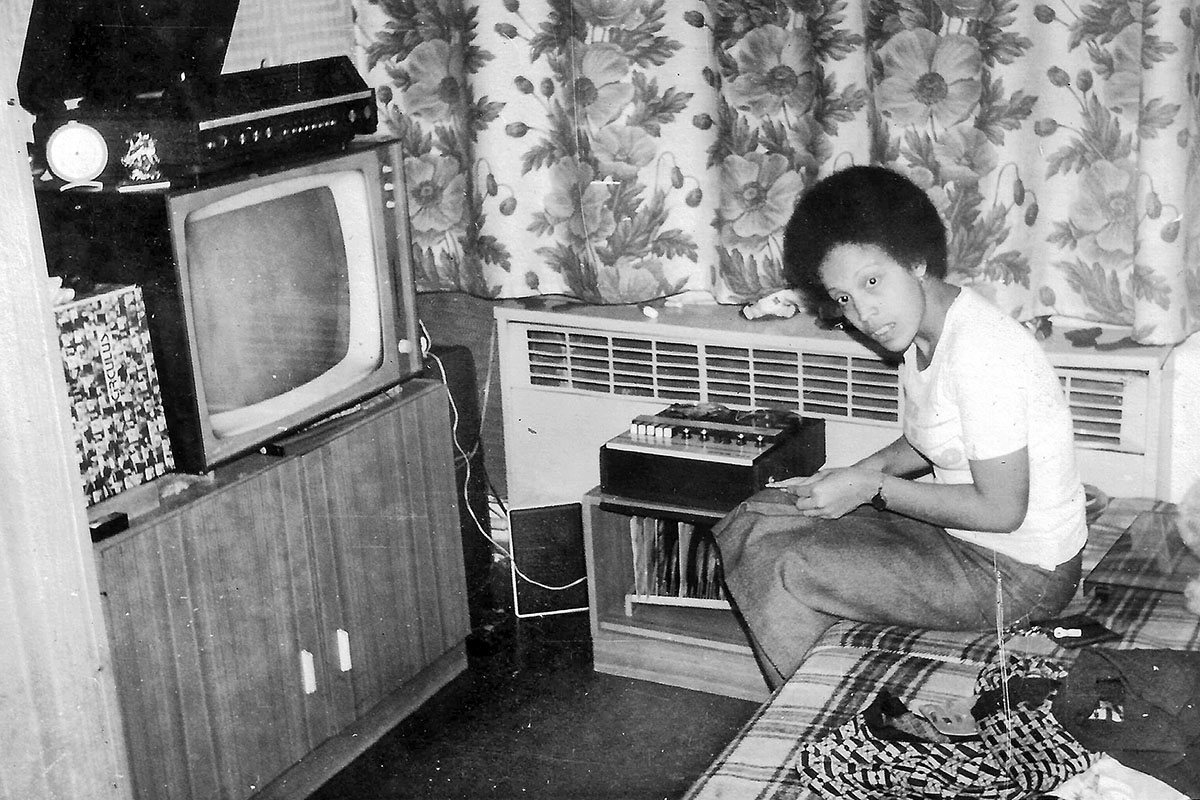

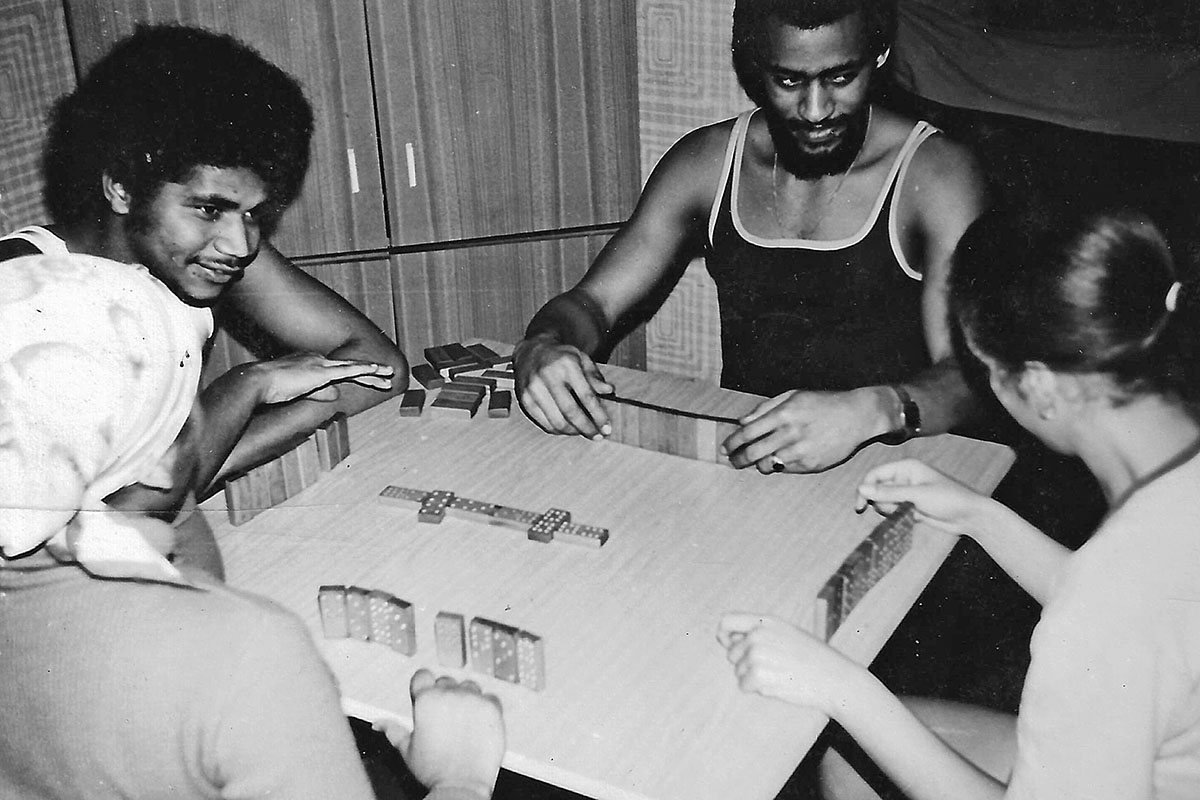

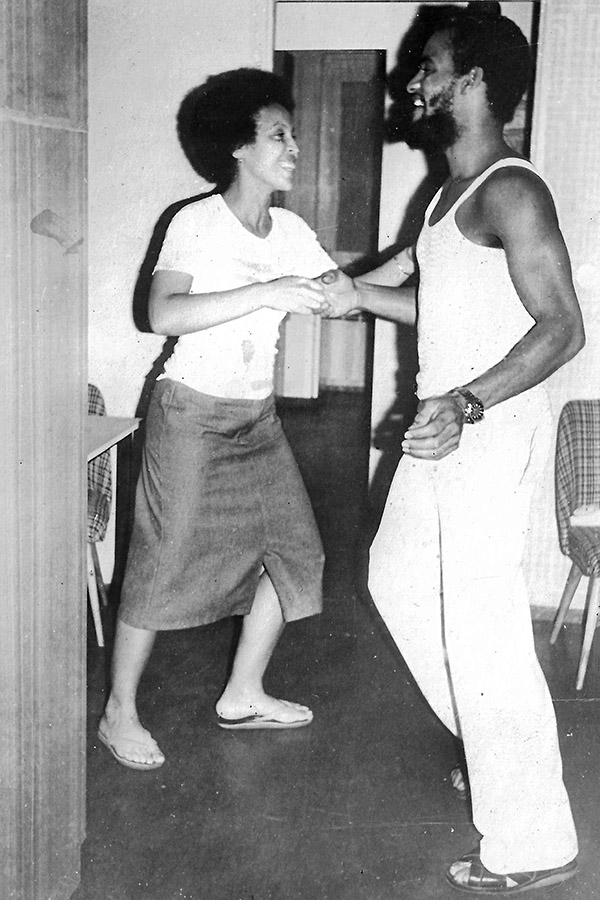

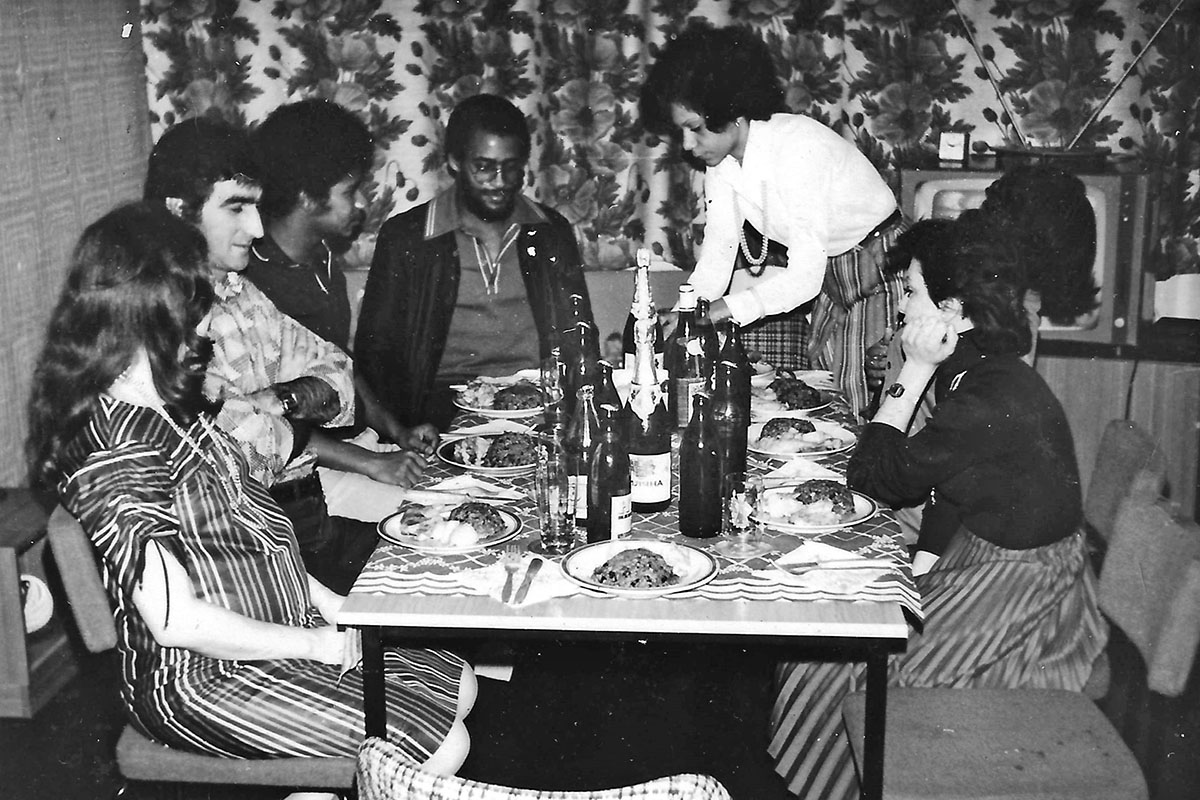

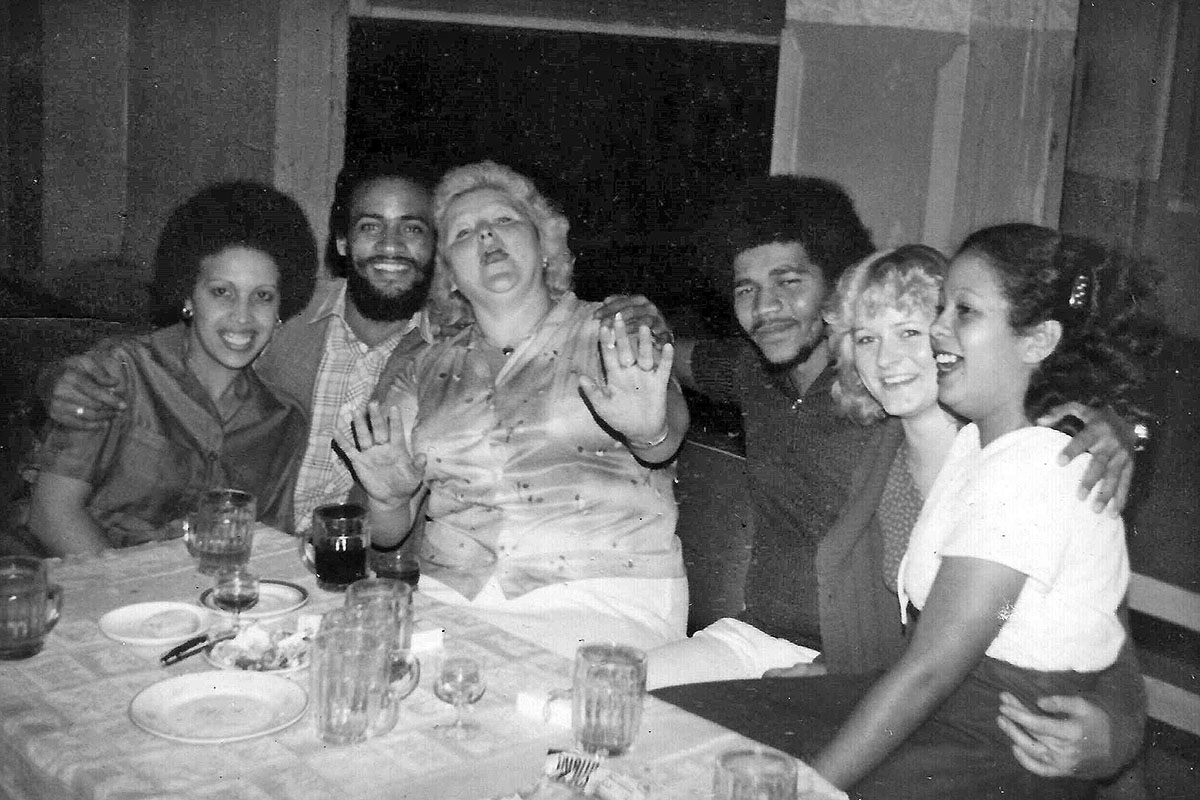

The four women in Yolanda’s group spend most of their time with other Cuban migrant workers. But there are also some Germans seeking contact. They spend a lot of their free time in the backyard of the residential home, hanging out with colleagues, playing volleyball or basketball.

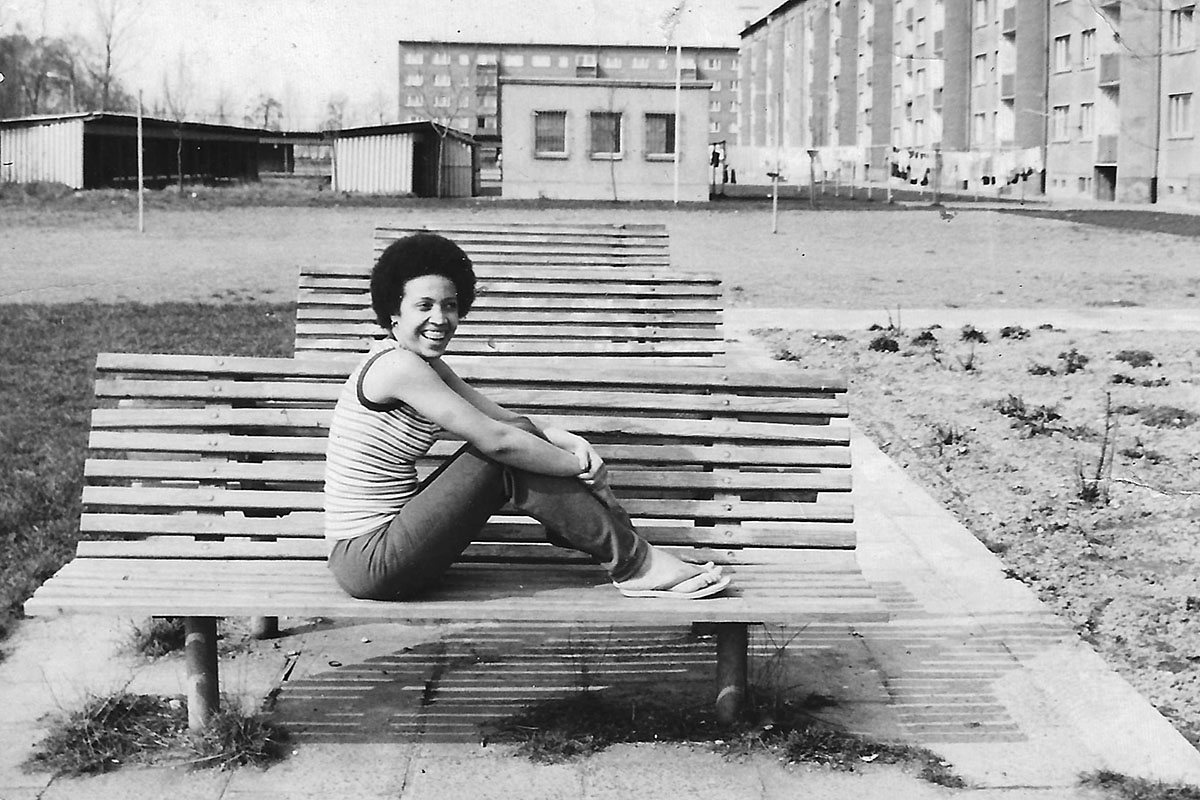

Everyday racism

Yolanda Cuesta’s appearance, her skin color, her hair are a constant topic. It gets too much. Again and again, people want to touch her, invade her space. Yolanda likes her looks and wears — like many of her Cuban colleagues — the Afro, called “spendrum” in Cuba. In Cuba, too, the hairstyle is an expression of black empowerment, popularized by the civil rights hero Angela Davis. In East Germany, it causes a stir and frequently disrespect. Yolanda resents the constant comments about her body, which often parade as compliments.

Sometimes it made me feel uncomfortable because people came up to me to touch my skin. And said something about the color of my skin.

Yolanda Cuesta Osloal, Havana 2021

Yolanda Cuesta recounts where and how she is confronted with racism in everyday life.

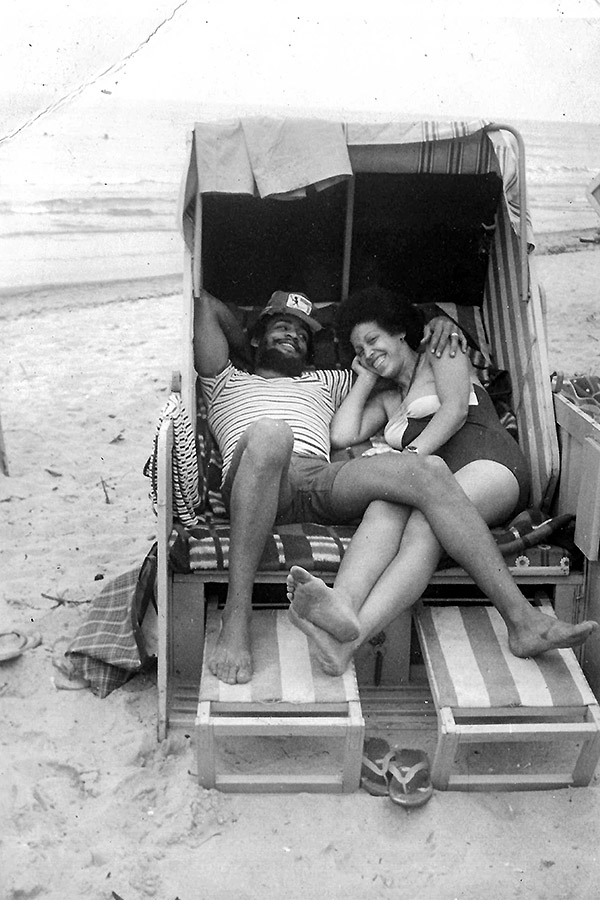

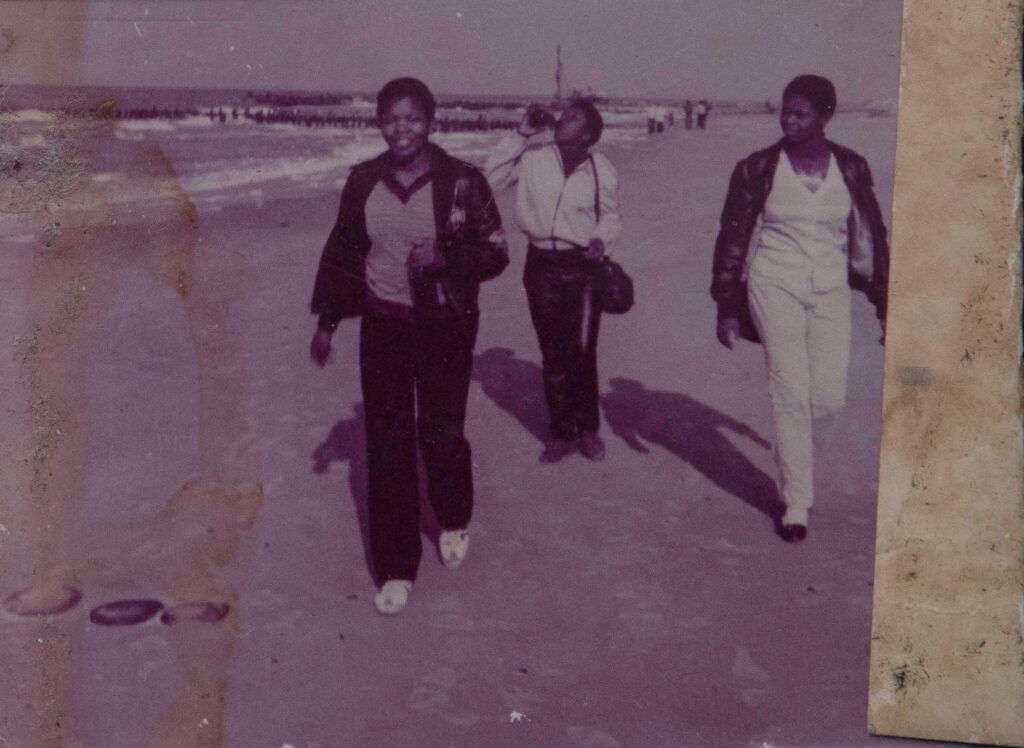

Summer is a good time for Yolanda. She enjoys the holidays, loves being by the sea and getting a tan.

Women and men

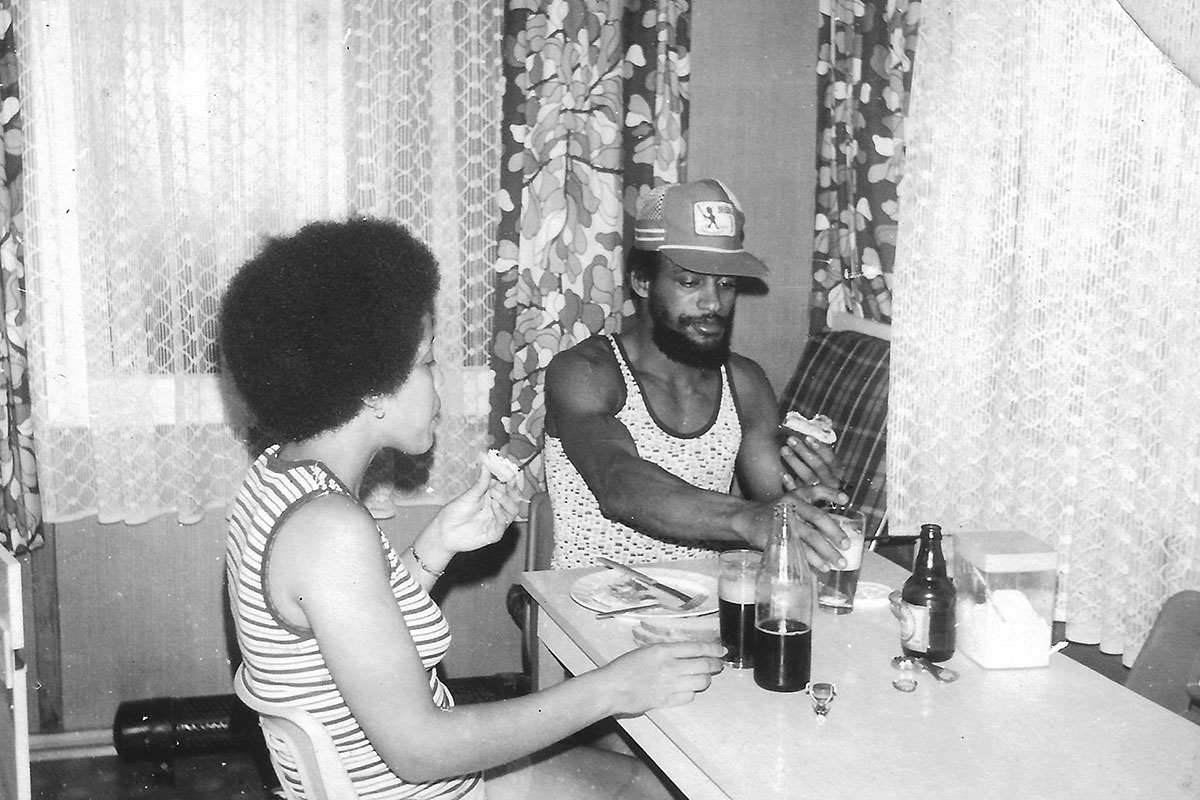

As time passes, more and more romantic relationships emerge between Cuban men and German women. A phenomenon Yolanda Cuesta explains with Cuban men being more affectionate, more romantic and having more sense for details than Germans. She and the three other women in her group have Cuban, not German partners. Yolanda fends off the advances of German men. She perceives racism in the interest the men show her. And the ratio of numbers probably also matters: there are 46 men and four women in her group.

She and her flat mates cultivate friendships with some German colleagues and neighbors. They invite them to Cuban food — the women cook — and parties to their flat. From time to time, they are also invited to their [German] colleagues’ flats, and there are always parties at work.

Migrant experience

As stipulated in the bilateral government Agreement on Qualification in Simultaneous Employment, Yolanda Cuesta’s stay ends after four years. She would like to stay on, to further qualify herself. Owing her work in the factory and her independent life in the GDR, she no longer agrees with some of the behavioral patterns in Cuba. She feels empowered and understands now more about the world. During an previous holiday in Cuba she was shocked by the rigid gender roles, the machismo.

It made us stronger. As a woman, as a person and in general.

Yolanda Cuesta Osloal, Havana 2021

Involuntary return

Yolanda Cuesta’s desire to stay cannot be realized. All contract workers must return after the expiry of the state-agreed length of stay. But Yolanda also has personal motivations: following the death of her mother, she must take care of her younger siblings and father. Moreover, she is five months pregnant. She considers her time in the GDR enriching. Following her maternity leave, she is looking forward to apply the skills acquired in the GDR to her work in Cuba. She and her colleagues hope that their expertise will be useful for Cuba. And she recounts the disenchantment upon her return: “There were hardly any machines to work with, just a small lathe— even I was wider than the lathe! Well, that was a let-down for the whole group, because hardly anyone of us could practice what we learned there.”

At the end of the day, her record is mixed: “Moving to Germany … was part of my life, after all it lasted four years, and then I had my own life.” At the same time, she understands that she was deceived. What she had been promised turned out an illusion. She emphasizes that luckily she enjoyed it, she got out to learn new things, and that she had fun in the GDR and got to know a different culture.

Yolanda Cuesta lives in Havana and works as an executive secretary in a research organization.

Credits:

Elaine del Valle Cala conducted the interview in Havana in 2021.

Text: Isabel Enzenbach

Research and research protocol photos: Elaine del Valle Cala, Isabel Enzenbach

Video edting concept: Isabel Enzenbach