Why De-Zentralbild?

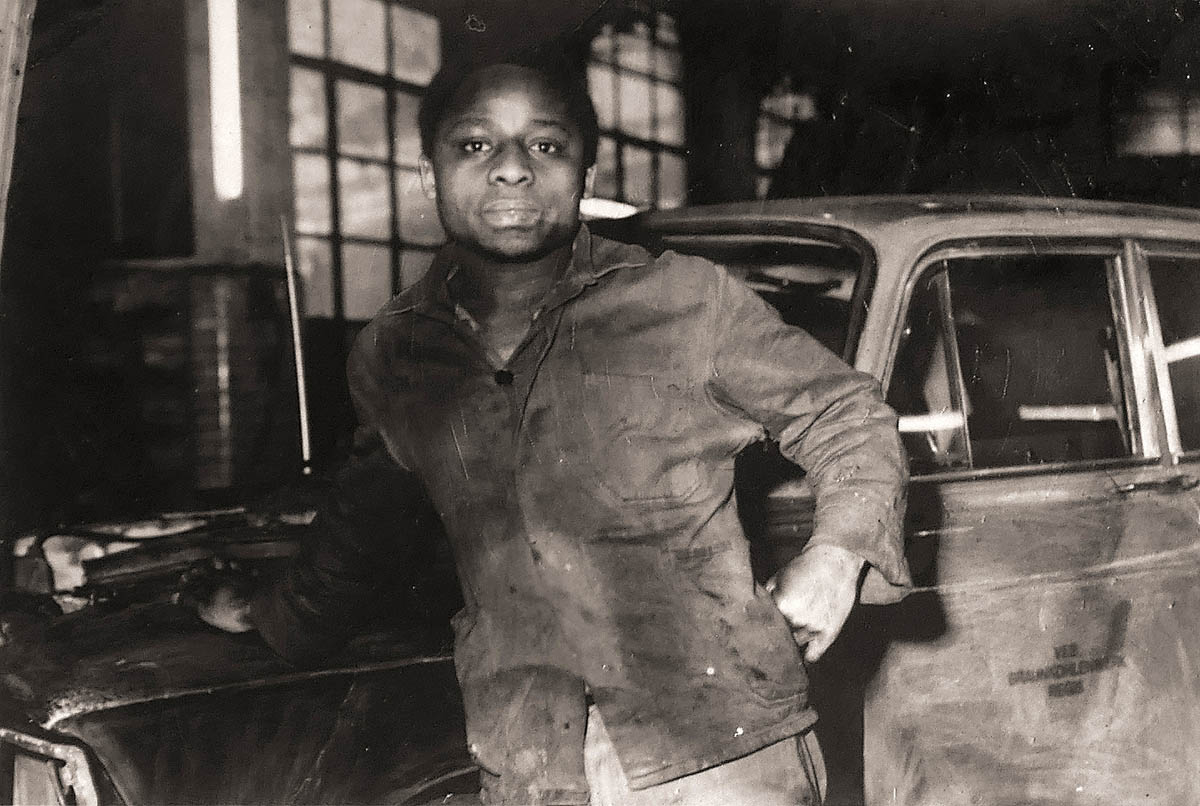

So far, pictures from the everyday life of former contract workers, international students or political emigrants in the GDR are widely unknown. Occasionally that even includes their own families, where the old photos gather dust in boxes and albums. They rarely make it into publications, museums or archives, despite the fact that they open up important perspectives on the history of migration to the GDR.

The Archive and Online Exhibition De-Zentralbild feature private photos of people, who have lived between 1957 and 1990 in the GDR. The pictures are linked with memories contained in those captured moments as well as with narratives about the life in East Germany. De-Zentralbild publishes and preserves photos that depict images of the migrants’ everyday life in the GDR, of private moments and situations, and represent them in the collective memory. Likewise, De-Zentralbild collects pictures and stories of people who voluntarily or involuntarily returned to their countries of origin. Their pictures and narratives also belong to Germany’s migration history.

DOMiD e. V. — Documentation Center and Museum on Migration in Germany — archives those photos and information on a permanent basis, for which the lenders have given their consent.

Zentralbild und De-Zentralbild

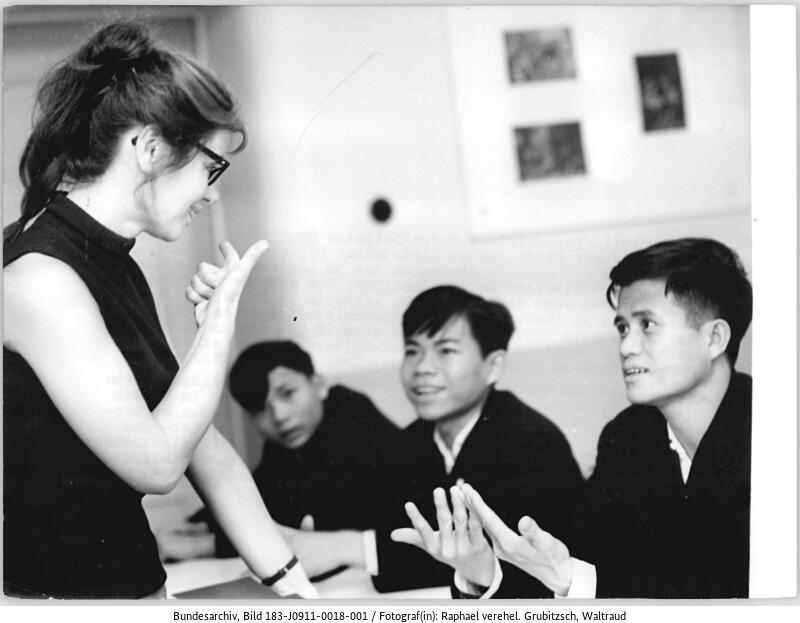

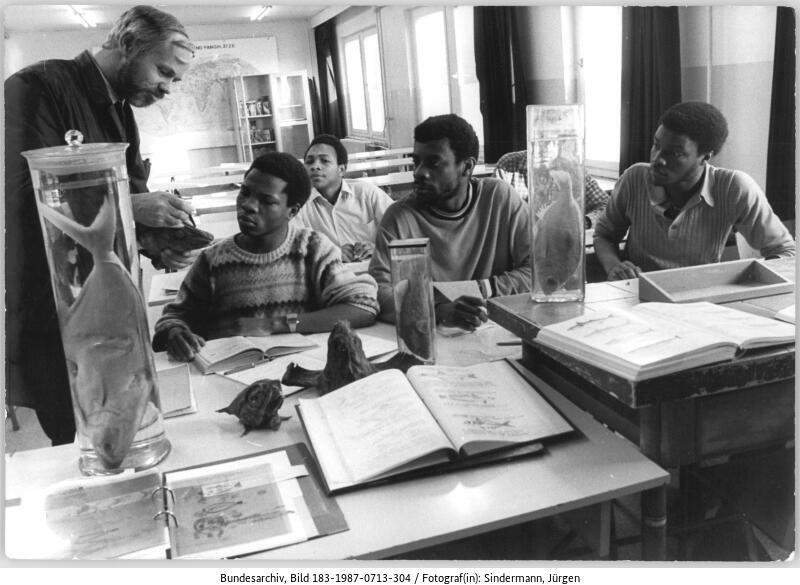

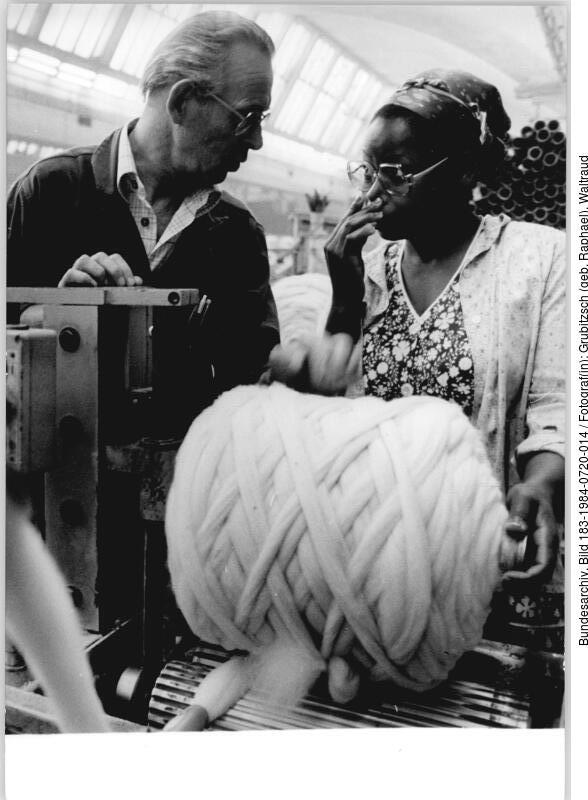

Founded in 1952, the East German state photo agency was known as Zentralbild; it was affiliated with the Allgemeine Deutsche Nachrichtendienst (General German News Service, ADN), the state news agency of the GDR, and supplied photos for almost all national newspapers. The fact that the GDR did not consider itself an immigration country is reflected in the stock of Zentralbild. Migration was always intended to be temporary only, and the immigrants were to fulfill above all the political, economic and ideological purposes of their stay in East Germany. Hence the photographers working for Zentralbild were expected to portray the GDR migrants in keeping with those purposes. Photos from the Zentralbild archive rarely ever show migrant everyday life, or people who can be perceived as »Ossis[1] of Color«. Much more often, the official agency’s photos staged how diligently international students study together with other international students; how German colleagues train contract workers in modern industrial facilities and teach them the ropes. The pictures taken by Zentralbild photographers were mostly intended to illustrate international solidarity. Even to this day, these photos remain popular. They are available free of charge for science and political education.

Before the end of this year, E. will finish her assignment in the GDR and return to her homeland.

From the original caption of the photo Zentralbil 183-1984-0720-014

De-Zentralbild turns around this perspective: we collect and display private photos of migration to East Germany. These can be viewed online in context with the memories of their owners, who now live in many different places around the world. Thus a decentralized narrative emerged, which can be accessed in five different language versions.

The term »private photos« refers to pictures that are privately owned. Often it is not known, who has taken them. Even though many students, contract workers or people who received asylum in the GDR took their own pictures, the provenience of a picture can rarely be established after such a long time. Private, analog photo collections usually consist of pictures taken by different people: pictures taken by oneself, pictures taken by relatives or friends, photos taken by professionals, such as a studio or wedding photographer. Some former contract workers have photos that were probably taken by plant photographers or members of the plant photo clubs, which existed in many GDR plants.

Likewise, private photos do not truly depict »how it used to be«. They too emerge with specific intentions — mostly to produce beautiful memories.[2] Therefore, there are typical motifs in private photography that can also be discovered in the collections of our photo lenders, such as portraits during the transition into a new life chapter, biographical highlights, celebrations or travels, pleasant moments outside of work, friendships or moments of happiness. When viewed in retrospective, they often produce positive feelings — as was intended. However, the motif of a picture does neither disclose the situation in which it was taken nor its meaning.

But the private collections of GDR migrants also contain photos that evoke associations of isolation, of being left to one’s/their own devices, of filthy work, boring events, or suffering. De-Zentralbild assembles rather diverse photos, not least because their owners lived in very different situations. As a result, the history of migration in the GDR takes on a multifaceted and contradictory aspect.

Old Stories or Current Issues?

Interview with Patrice G. Poutrus

Patrice G. Poutrus has a Ph.D. in history. He has researched the economic and social history of the GDR as well as migration and flight in both German states during the Cold War, memories/memoirs of the end of the GDR, the East German political upheaval and transformation. Currently, he is a Visiting Professor at the Center for Interdisciplinary Women’s and Gender Studies (ZIFG) at the Technical University of Berlin.

Isabel Enzenbach: What is, in your opinion, the relevance of studying migration in the GDR for the present day?

Patrice G. Poutrus: For all countries organized as nation states — and as such the SED leadership wanted its state/the GDR to be considered — the societal changes resulting from migration posed and still pose a crucial challenge. Both, flight as well as immigration, force nation-states to develop criteria for belonging and non-belonging, and thus a variety of regulatory mechanisms that impact immigrants as well as natives and their courses of action. This problem manifested itself in a remarkable way for the GDR. And although the GDR can be characterized much more clearly as a society of emigration rather than immigration, the SED state also faced these challenges, especially in the last years of its existence. These conditions, their specificity and their persistence from the GDR history, allow us to understand the current conflicts about flight and migration in East Germany.

I.E.: What are your main objections to the GDR migration regime?

P.G.P.: My political criticism is that migration relations in the GDR were not guided by norms such as internationalism, solidarity and friendship among peoples. True, the representatives of the SED state issued abundantly such pronouncements in the context of labor migration. Yet the decisions made in this context were marked by the exploitation of political dependencies, assumptions of economic utility, and implicitly —and sometimes explicitly — by national chauvinism and racist resentment on the part of the GDR. For people from crisis and war zones, this may and will appear acceptable to a certain extent, nor can they be blamed for it. From a postcolonial and human rights perspective, however, the migration practice of the SED state is just another, albeit remarkable, case of double standards towards people from the Global South.

I.E.: What correlation do you see between the attitude of the GDR regime or GDR society respectively, and the current racism and violence migrants experience today in East Germany? In fact, when a liberal, open immigration society is concerned — don’t prevail “all-German” problems?

P.G.P.: The debate about conditions in East Germany, and not just in the context of migration, is characterized by an idiosyncratic paradox: There is a strong narrative of the loss of the good old days, but criticism of this position is readily and often denounced as a SED/MfS method. In my opinion, this is a dead end — socio-politically as well as memory-culturally. In principle, my starting point is that there was no »zero hour« for East Germany or East Germans in 1990, just as there was no such thing in 1945. However, people do respond to truly dramatic changes within the framework of their existing norms and proven practices. These may become radicalized, but they do not simply emerge out of the situation, and this is another reason why they are passed on intergenerationally. In my opinion, the assumption that people react to external stimuli or impositions in a quasi-reflexive manner is problematic, because it is simplistic and also ahistorical. In particular cultural studies of migration have revealed that in times of great social and economic changes/challenges, people tend to rely on their traditional knowledge and cultural practices, or to protect them. Based on this, I am convinced that migrants, East Germans and other people in crisis situations are no social robots after a societal reset, but that their behaviors are historically shaped. Contemporary interpretations that dispense with or deny this perspective do not aim at critical explanations of social conditions, but at their justification in terms of identity politics. The latter, however, is a pattern of action that has a long tradition, especially in recent German history.

I.E.: One of the former Mozambican contract workers, who today works in South Africa, recently told us that his colleagues point-blank refuse to believe his GDR stories. Coming from an African country by plane to Europe and immediately getting a work permit and decent accommodation for little money, ha ha ha, that can’t be true.

I.E.: Hence my question: Isn’t this a concluded era, a migration model that serves at best as a questionable contrast for current issues?

P.G.P.: No doubt, the era of semi-liberal labor migration from Africa to Europe has been over for several decades. However, bilateral agreements such as the one between the GDR and Angola can only be considered from an abstract perspective as part of this superseded migration regime. Labor migration to the GDR took effect at a time when active recruitment in Western Europe had almost completely ended. The above described conditions were framed in a very restrictive system of selection and control mechanisms by the SED state; these conditions were considered temporary and granted little to no rights to the individual life ambitions of labor migrants. In this sense, the labor migration practiced in the GDR would probably be considered an acceptable model by conservative domestic politicians in the old and present-day Federal Republic. The fact that conditions in the GDR appear acceptable to contemporary witnesses in contrast to more recent developments is no merit of the SED state.

I.E.: Some of our interviewees have raved about their life in the GDR and the conditions they encountered there. “The best years of our lives” is a quote that encompasses this. How do you interpret such statements?

P.G.P.: The topos “the best years of my life” was and is omnipresent in the memoirs of people from the “Age of Extremes”. It arises among veterans of the World Wars and revolutions, among many supporters as well as fellow travelers (Mitläufer) of overcome dictatorships, and even among some of the victims of this modern form of rule. Therefore, these statements are less surprising in the case of migrant workers and reveal something about the contradictory, if not difficult life paths of the narrators. Seeing opportunities ahead of oneself is always more pleasant than having lost them. In this sense, it seems to me as a historian neither appropriate to intervene against these biographical narratives, nor to advocate for these contemporary witnesses. The challenge, in my opinion, is indeed to put personal experiences and social conditions into a plausible relationship and not to set them off against each other.

Das Interview wurde im Mai 2023 schriftlich geführt.

The team

There are many people behind De-Zentralbild:

Concept and artistic direction

Dr. Isabel Enzenbach, Julia Oelkers

Research and interviews

in Mozambique

Catarina Simão, Julia Oelkers

in Vietnam

Trần Bảo Ngọc Anh, Prof. Dr. Phạm Quang Minh

in Cuba

Elaine del Valle Cala, Isabel Enzenbach

in Germany

Nguyễn Phương Thúy, Nguyễn Phương Thanh, Jessica Massóchua, Julia Oelkers, Isabel Enzenbach

Texts and editing

Isabel Enzenbach, Julia Oelkers

Design

Susanne Beer (2019-2023 Zoff Kollektiv)

Development

Marc Wright

Photo editing

Hermann Bach, Umbruch Bildarchiv

Videos

in Mozambique

Director/Interview: Catarina Simão

Camera/Sound: Amâncio Mondlane, Humberto Notiço, John Pitta

in Vietnam

Director/Interview: Prof. Dr. Phạm Quang Minh

Camera/Sound: Lê Ngọc Anh

in Cuba

Director/Interview: Elaine del Valle Cala, Havanna

Camera/Sound: Luis A. Guevara Polanco, Klaus Westermann, Alfonso Fontenla, José Armando Amat

Production: Juan Caunedo Domingos, Elaine del Valle Cala (Champola producciones)

in Germany

Director/Interview: Julia Oelkers, Nguyễn Phương Thúy, Jessica Massóchua

Camera/Sound: Arne Janssen, Lars Maibaum, Thomas Walther, Olaf Bublitz

Technik: Robert Jahn

Animations/Collages

Collages: Susanne Beer (2019-2023 Zoff Kollektiv)

Animation Collages: Nguyễn Phương Thanh

Sounddesign: studio lärm

Editor

Lucian Busse

Translation:

Texts: Birgit Kolboske, Luu Bich Ngọc, Ngọc Mai, Maria-João Manso, Fernando de Almeida, Iveth Cuenca González

Videos: Babelfisch Translations

Contentmanagement

Mimosa Akbal

Proofreading

Katharina Wüstefeld,

Financial consultant

Niels van Wieringen

Head of production

Thomas Walther

We thank for sharing their memories and leaving photos and documents:

Amílcar Cubillo Medrano, Amissina Namagere Selemane, Annette Hannemann, Augusto Jone Munjunga, Bobby Díaz Gurriel, Đặng Thị Thìn, Danilo Starosta, Esmireldis Navarro de la Cruz, Francisca Raposo, Geraldo Paunde, Humberto Cala Pérez, Ibraimo Alberto, Jesús Ismael Irsula Peña, Kostas Kipuros, Mansar Asisi, Mona Ragy Enayat, Nguyễn Thị Thu Thuỷ, Pham Thanh Ha, Regina Veracruz, René Castellano Ponce, Sergio Majope, Tanju Tügel, Teresa Cossa, Tomás Django, Trần Thanh Hương, Trần Thị Thu Hương und Nguyễn Phùng Quang, Vũ Thanh Điệp, Warter Hechavarría Duany, Yolanda Cuesta Osloal

Sincere thanks to Aghi, for the collegial exchange and research photos, to Bengü Kocatürk-Schuster, Dr. Robert Fuchs and Dr. Katrin Schaumburg of DOMiD e.V. for the long-term archiving and dissemination of the photographs. For indispensable help with research, video recording and editing in the countries of origin, we thank Elaine del Valle Cala and the team of Champolafilms, Felix Zühlsdorf and Dieter Müller (in Cuba), Catarina Simão and Caroline Brugger (in Mozambique) and Philip Degenhardt and Trần Bảo Ngọc Anh ( in Vietnam). Sincere thanks also to Prof. Dr. Patrice Poutrus and Prof. Dr. Maisha M. Auma, Prof. Dr. Hanna Meißner, Peggy Piesche and Dr. Jane Weiß.

We thank our funding institutions and cooperation partners for their collegial cooperation and generous support: to the imprint