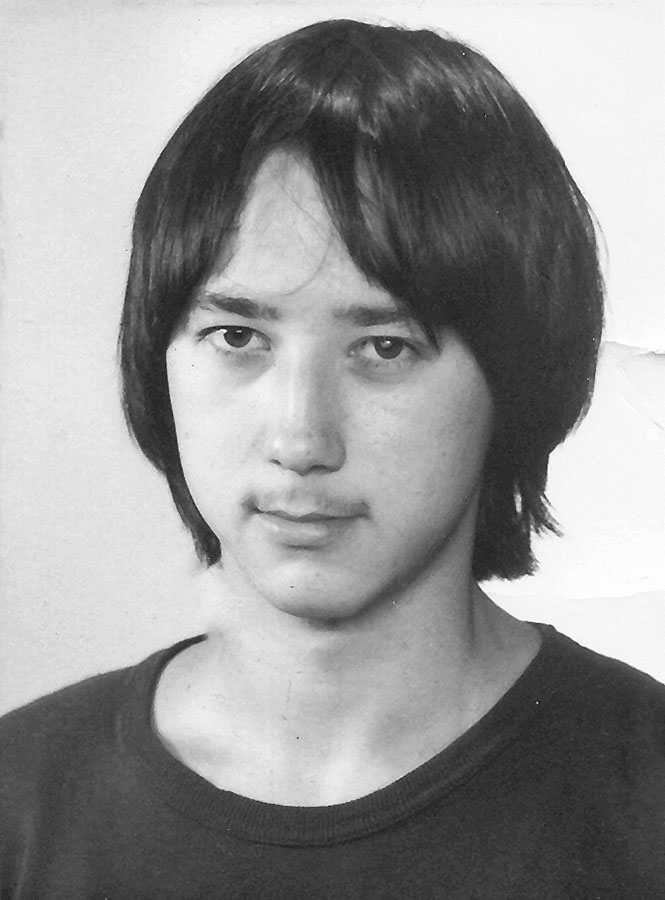

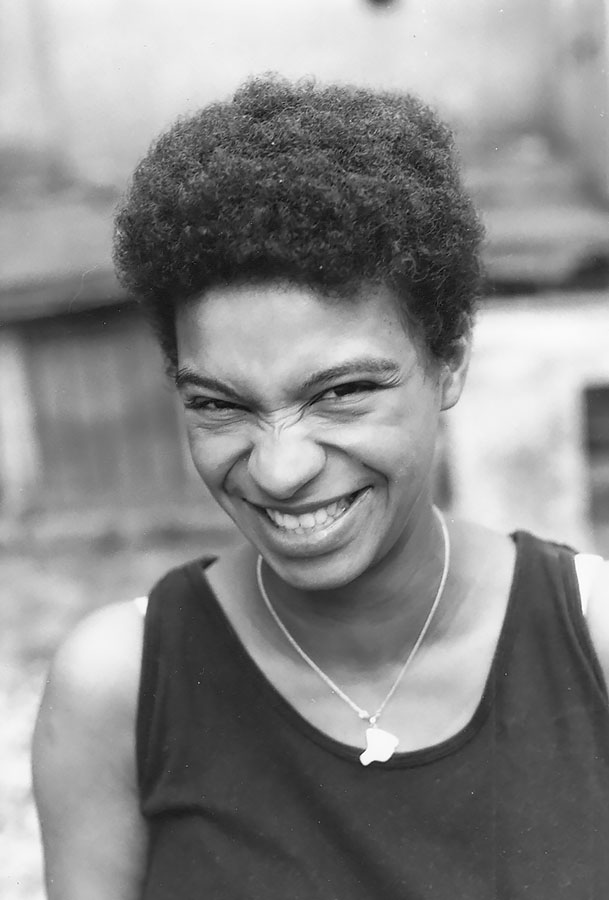

Danilo Starosta

During the 1960s and 1970s, Danilo Starosta grows up in a small town in Saxony. His mother is a student, his father a contract worker. His father returns to Mongolia before Danilo is born. Danilo spends most of his childhood with his grandparents.

The Sixties in the backwoods

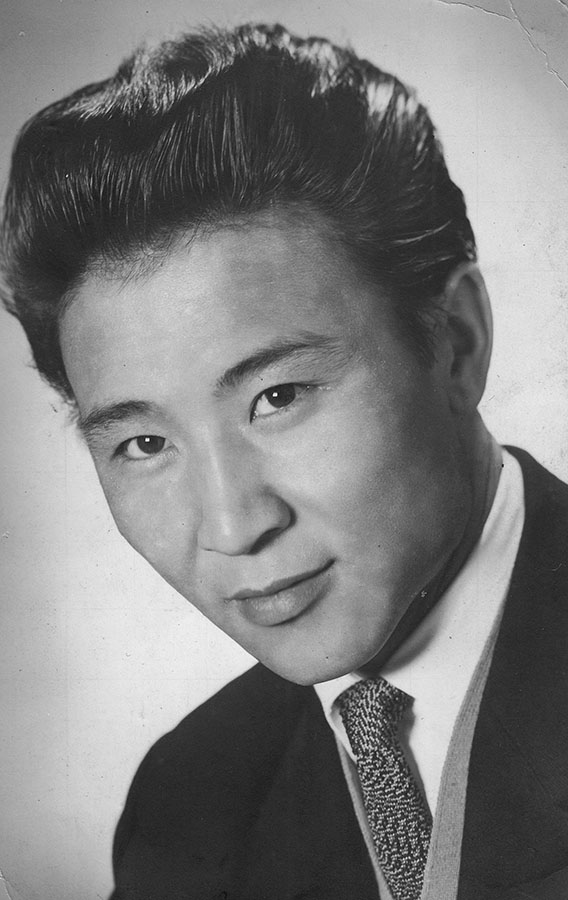

Danilo Starosta is born in Freital in 1965. His mother studies economics and subsequently works in various companies in leading positions. His father belongs to a group of Mongolian contract workers, who came to the GDR in 1962 to learn technical trades. He is employed as a translator at in the large-scale printing combine Völkerfreundschaft in Dresden. For a long time, Danilo only knows his father from a photo.

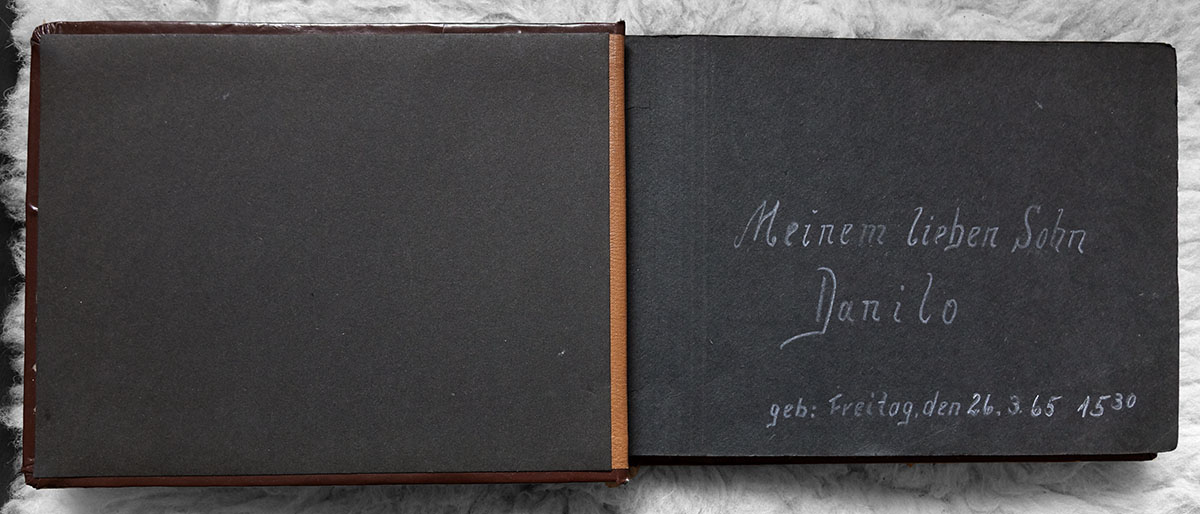

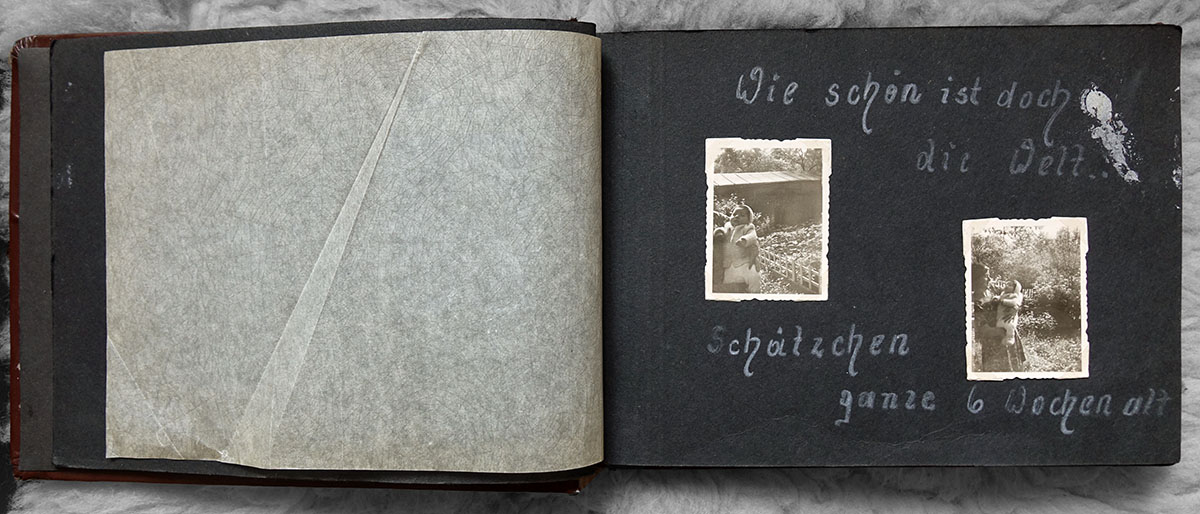

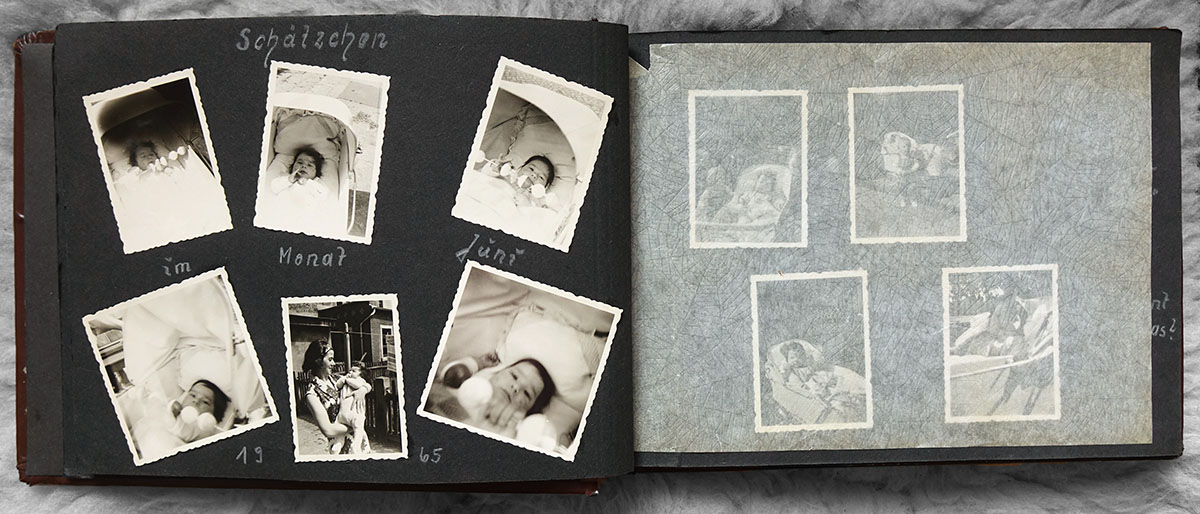

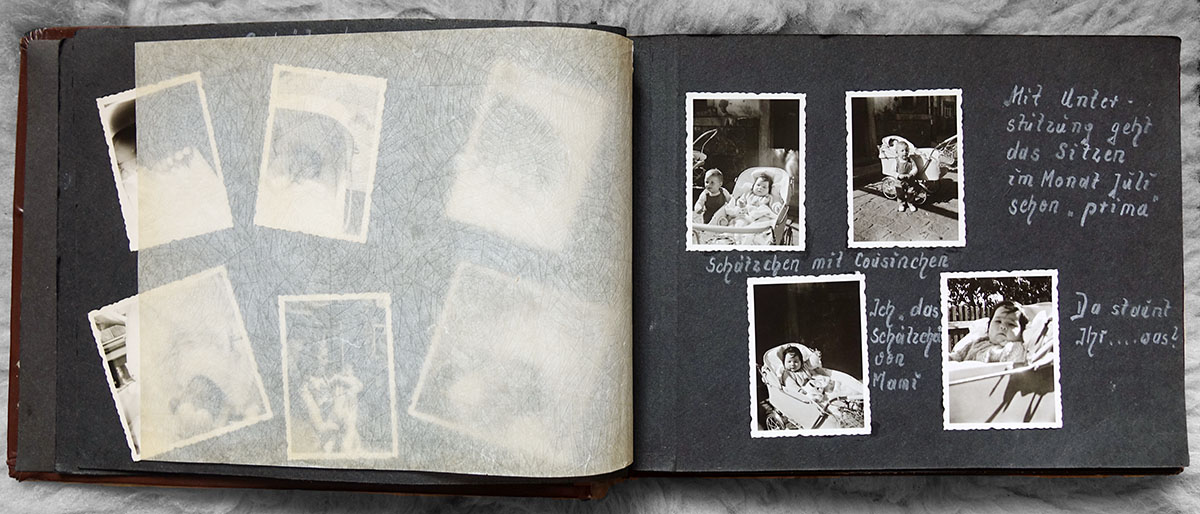

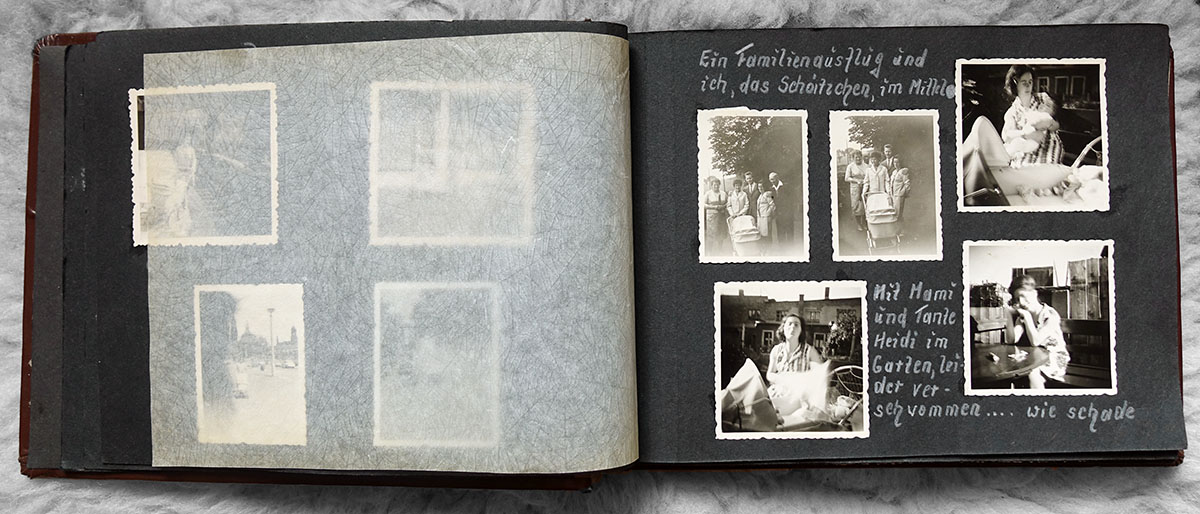

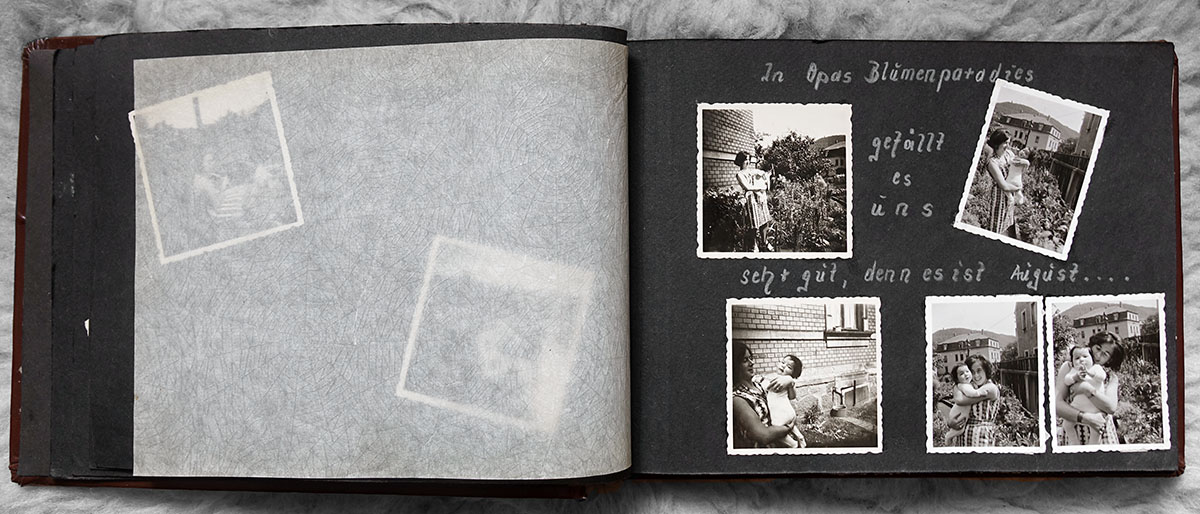

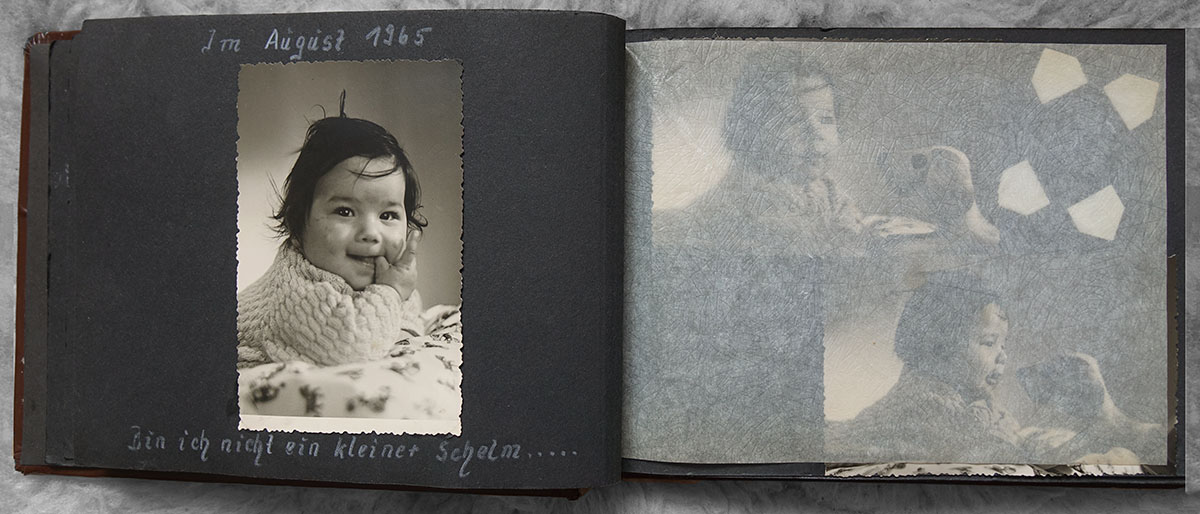

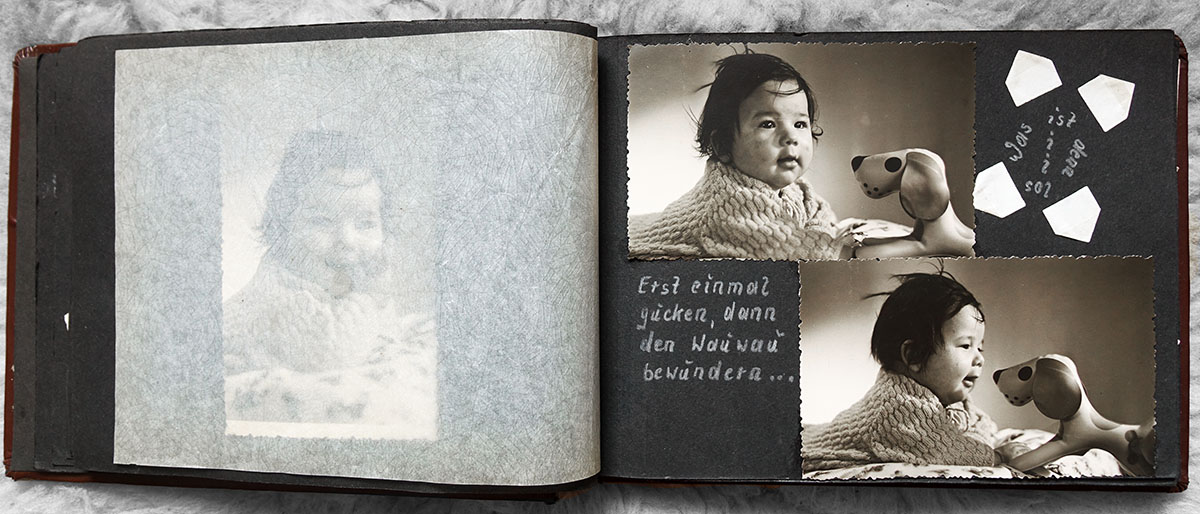

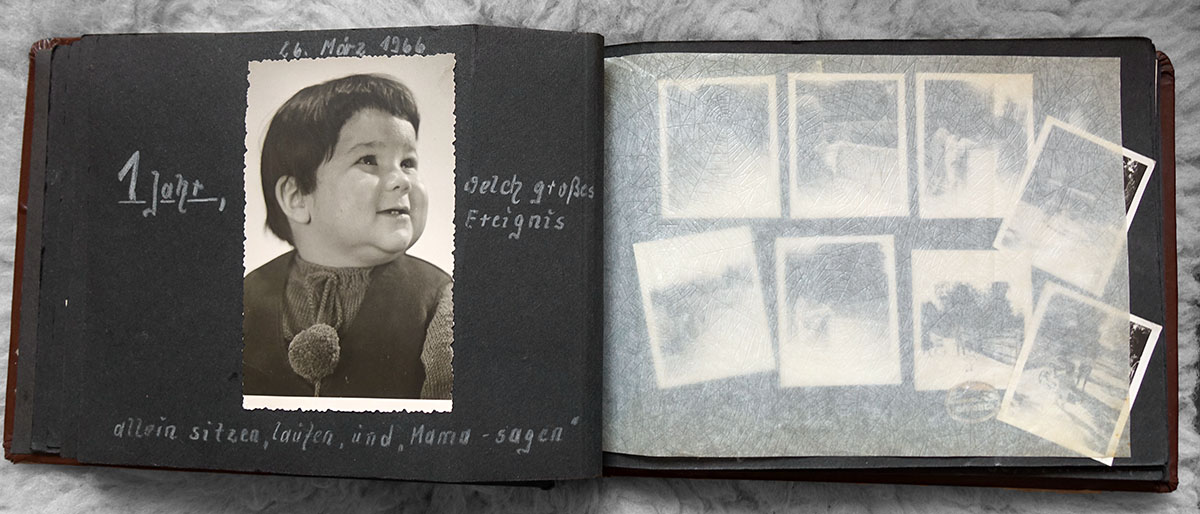

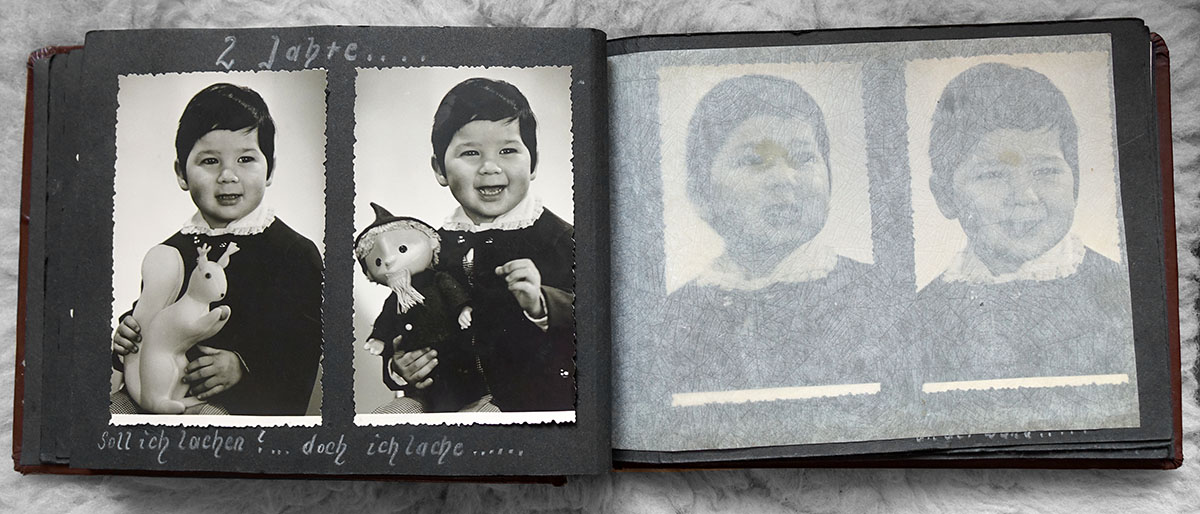

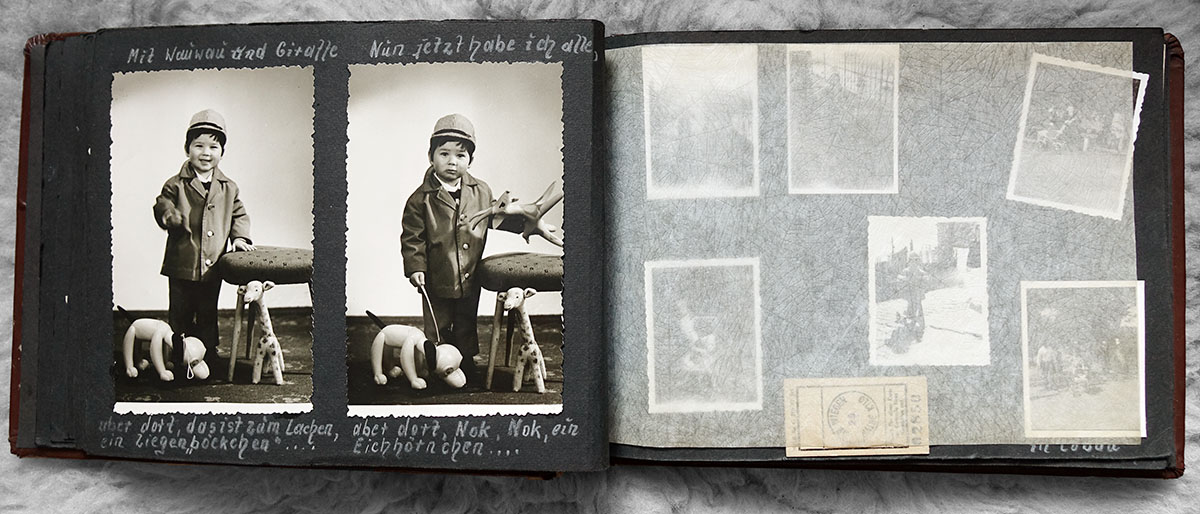

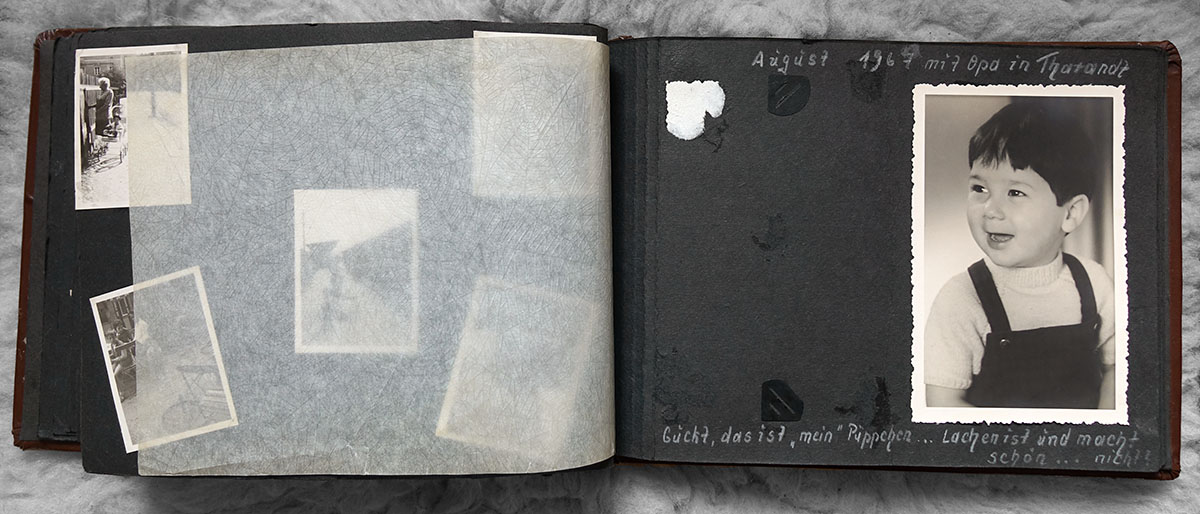

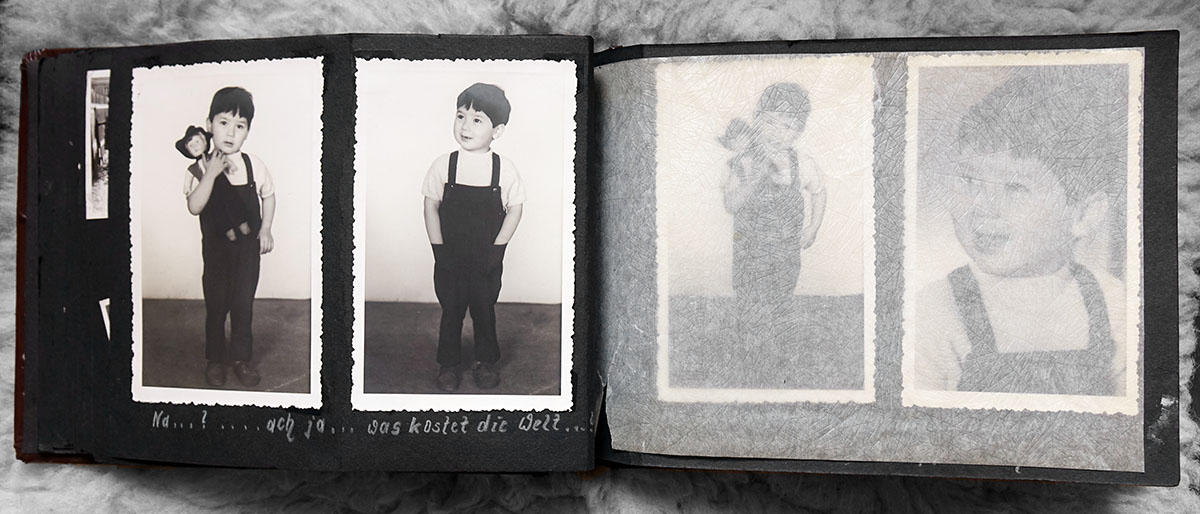

Picture book of a childhood

Danilo Starosta grows up as an Asian-perceived child without his father as an attachment figure in a white and, as he says, “very petit-bourgeois” family in provincial Saxony. His development as a child is documented in many photographs. The mother lovingly arranges the pictures in an album. Grandfather Kurt Klämbt regularly takes his grandson to a photo studio. Another motive for the pictures is to send them to Danilo’s father in Mongolia. Kurt Klämbt has his own camera. As he has taken most of the family photos he is usually not pictured.

The grandparents are firmly rooted in the community of Freital. The grandfather runs a restaurant destination. The grandmother is a trained typesetter, but stays at home after the birth of her six children. “My grandpa was a well-known person in town,” Danilo Starosta says. He has a very close relationship with his grandparents, especially his grandma. They take care of him, because Danilo is denied a kindergarten place. The kindergarten teachers feel unable to integrate him. They tell his mother, they are afraid that he will be bullied by other children. Therefore, Danilo is hardly ever together with children of his own age until he starts school.

As a matter of fact, I was stigmatized as your typical foreign kid.

Danilo Starosta, Dresden 2022

Danilo Starosta talks about racist stigmatization at school and receiving awards at the children’s carnival.

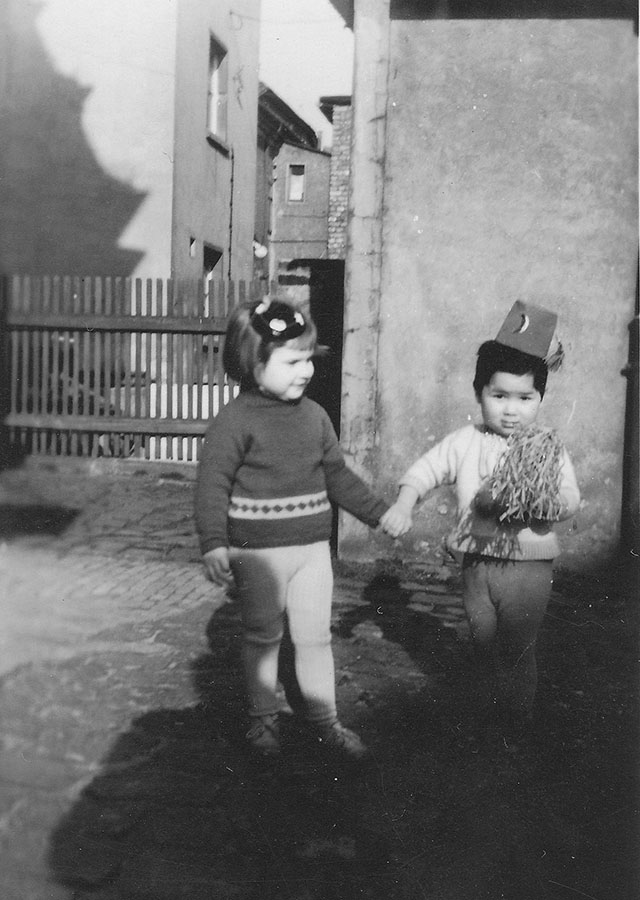

Clothes make the man

During carnival time, Danilo Starosta is a success with the costumes chosen for him by the adults. Several times he receives prizes for the best costume as a “Chinese” or “Turk”. When he is about ten years old, his grandmother sews him his dream costume “Musketeer”. That year he does not win an award.

Blend in by all means!

Hoping to protect Danilo against exclusion, his family likes to dress him in traditional and typically “German” garments. Thus they hope to make him less conspicuous. His black hair is hidden under hats or caps. But the other children don’t wear such clothes, which are considered outdated even then. Instead of blending in with the group, Danilo stands out even more in his leather trousers and loden jackets.

When Danilo Starosta starts school, he can already write and do math. He can’t play, however, dodgeball or football. The team spirit that other children have learned in the group at kindergarten is new to him. For the first time, he has to find a place among his peers. On the teachers’ recommendation he does not go to the day-care center, but is picked up after school. This is to protect him from being teased by other children. One bright spot in this situation is his teacher, Mrs. Rautenstrauch. “She didn’t care what I looked like,” says Danilo Starosta. She leads the theatre group and casts the main roles with him. He doesn’t speak Saxon dialect, and he can memorize a lot of text quickly. She introduces him to a new world outside the family.

I grew up behind a very petit-bourgeois façade.

Danilo Starosta, Dresden 2021

Danilo talks about his brother and the very close relationship to his grandma Lisbeth.

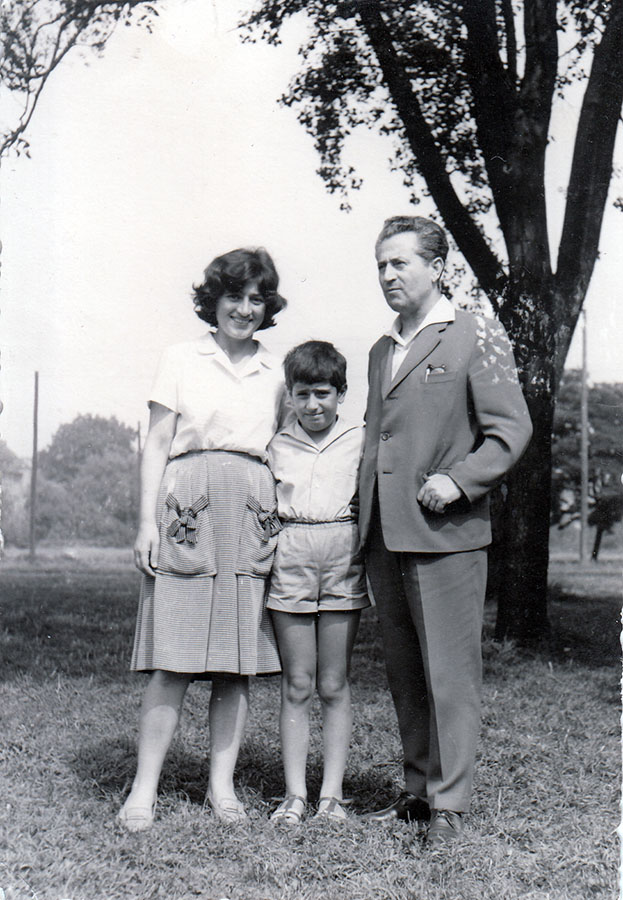

Sunday excursion

The grandparents really liked this picture, says Danilo Starosta. It shows the family at their favorite destination:

“This view, the Prager Straße with the Dandelion fountains. That was this generation’s confirmation that socialism wasn’t all wrong. National Socialism, yes, that was wrong. But about socialism: air, light, you can go places, you don’t have to be super rich and still can feel good. That was super important for that generation. […] You could always pose as petit bourgeois, that’s the typical façade. We had no money, or little, but it was all right. You could still be out there, and have an ice cream with your grandchildren in the Café Prag,” says Danilo Starosta.

Books are his lifeline

Danilo devours books. In Chinghiz Aitmatov’s books he discovers heroes, who look like him. For the first time he has role models. Likewise important for him is the contact to Soviet soldiers. “There were a lot of Asian faces there, and they saluted me. They probably thought I was the child of one of their people.” As a teenager, Danilo begins to challenge stigmatization. Together with others he takes action against racist attacks by neo-Nazis. The 1990s he experiences as extremely violent.

Danilo Starosta becomes a social worker and is committed to emancipatory coexistence and against any kind of racism. He never met his father, but today he is in close contact with his sisters in Mongolia.

Danilo Starosta lives in Dresden and works for the Kulturbüro Sachsen.

Credits:

Julia Oelkers conducted the interview in Dresden in 2022.

Text: Julia Oelkers

Research and research protocol photos: Nguyễn Phương Thúy

Video edting concept: Julia Oelkers